更新市區還是更遜市區?|How can we use urban renewal as a tool, not a weapon?

在先前兩篇吉事,我們聚焦討論了市區更新的目的及多元模式,破解市區更新等同重建的迷思,並透過幾個海外案例,探討市區更新應如何回歸以人爲本——以盡量保留現有城市面貌和社區脈絡為基本,改善舊區生活環境及回應居民需要為首要目的。回望本港近年的市區更新項目,又有否善用市區更新,真正解決都市衰退問題嗎?

深水埗「棚仔」清場:現行制度下,民間方案所謂何物?

俗稱「棚仔」的深水埗欽州街臨時小販市場於2023年1月31日正式關閉。雖然「棚仔」為全港碩果僅存的布市場,但在2015年,食環署卻在未有諮詢公眾的情況下提出永久清拆「棚仔」,以騰空用地供房委會作興建公屋之用。

由2015年至今共8年間,布販們亦為了「棚仔」而付出了許多。除了與民間團體合作舉辦導賞團、市集和時裝展等,更成立了深水埗參與規劃平台(下稱規劃平台),連同一衆城市規劃師、設計師與布販、顧客、深水埗地區團體、居民等持份者一同舉行了兩輪社區規劃工作坊。縱使布販大多希望不遷不拆,當時也探討了其他可能性,並就集體搬遷、可負擔租金等基本安置要求達成共識。及後,規劃平台更以政府的搬遷方案為基礎,就新址通州街橋底臨時街市,擬備了一份名爲「棚仔社區布藝時裝中心」的民間替代方案,建議將新「棚仔」打造成一個集零售市場、社區、布藝和時裝中心等功能於一身的空間。當時方案更獲得澳洲 Wendy Sarkissian Courage Award「勇氣及社區參與獎項」及香港規劃師學會2017年獎銀獎。

然而,民間的努力似乎無法動搖政府部門清拆「棚仔」的決心。雖然平台在2016年6月向政府提交替代方案,亦曾與區議員及相關部門商討,但一直毫無進展,而食環署其後仍繼續提出將布販按「牌照」劃分資格的安置方案,惹來分化之疑。直至2018年,商務及經濟發展局公佈將在「棚仔」附近的通州街設立樓高五層的設計及時裝基地(基地),旨在「培育本港新晉設計人才及時裝設計師」。事實上,基地部分構思與民間替代方案有不少相似之處,尤其就提供共用設施、時裝製作空間等,但卻對布販的安置及其他安排隻字不提,更指「基地目標、對象同『棚仔』唔一樣」,亦似乎缺乏替代方案所提倡的社區關懷。最終,在「棚仔」49個「合資格」布販中,只有16位選擇接受食環署的搬遷方案,而其餘33位及其他「不合資格」布販則只能黯然離場。難得有如此豐厚的社區資本,但卻依然受官僚體制所限,選擇閉門造車而非把握機會與民合作,實屬可惜。

房委會清拆工廈:研究報告説了算?

遺憾地,「棚仔」布販的情況並非孤例。同樣面對類似情況的還有房委會轄下工廠大廈的租戶們。因應2019年施政報告建議,房委會於2021年完成有關清拆重建旗下工廠大廈為公營房屋的研究,並宣佈將清拆4座出租率達九成七的工廠大廈:九龍灣業安工廠大廈 、火炭穗輝工廠大廈、長沙灣宏昌工廠大廈及葵安工廠大廈。而租戶必須於2022年11月底前遷出,可選擇競投房委會其餘兩棟工廠大廈的空置單位,或自行於私人市場另覓單位。但由於不少租戶需要額外空間安置工業用重型機械,搬遷、裝修等費用動輒數以十萬計。然而,一當房委會宣佈清拆,私人工廠大廈單位租金隨即飆升,再加上部分租戶或會在作業過程中產生噪音,能另覓安身之所的租戶實在少之有少,因此不少都被逼結業或賣盤。

就如「棚仔」的布販,受影響租戶自2021年六月起組成了「四廠聯盟清拆關注組」,多次爭取不遷不拆,甚至提出「拆三座、保一座」的折衷方案等,但一年半來的努力最終仍以失敗告終。而過程當中相關部門亦未有主動向租戶諮詢,也未有與租戶們建立雙向溝通、商議的渠道。清拆重建牽涉衆多租戶,尤其觸及工業手藝傳承等議題,而部分更是主要製造商或供應商,若能提早著手與租戶接觸和溝通,甚至是在研究階段已開始與受影響租戶共同制定安置方案和支援政策,或許可將影響減至最低。

土瓜灣重建:何謂重建價值?

與香港常見的重建案例不同,在土瓜灣不少「十三街」的居民多年來都在爭取重建。不少樓宇都為結構安全問題所困,尤其部分為上世紀60年代興建的「鹹水樓」,隨著混凝土中的海水一直腐蝕鋼筋,居民都擔心自己所住的大廈會像當年釀成四死兩傷的馬頭圍道坍塌事故般倒塌,亦希望政府能夠主動重建大廈。儘管如此,近年市區重建局在土瓜灣展開的多個重建項目均未有包括「十三街」,而當被問到爲何未有就「十三街」及鄰近的「五街」,市建局行政總監韋志成直言樓宇收購成本高達400億元,就市建局目前財政狀況,需要先「儲夠錢」才可以開啓重建工作,並指業主應自行做好樓宇復修工作。然而,時隔數月,市建局卻在2022年10月宣佈斥資過百億元啟動臨近啟德的「五街」(即明倫街 / 馬頭角道發展計劃 ) 及「土瓜灣道/馬頭角道」兩個重建項目,而「十三街」則依然未有重建時間表。隨即引來不少居民質疑比起市民的居住狀況,市建局其實更重視兩片臨海地皮的發展潛力。而值得一提的是,在土瓜灣港鐵站一帶亦曾有已完成復修不足6年的大廈,甚至是仍在進行樓宇復修、結構良好的大廈被納入重建範圍(詳見土瓜灣靠背壟道 / 浙江街項目、土瓜灣道 / 榮光街發展計劃)。雖然同在土瓜灣,但開展重建項目的標準卻似乎截然不同,實在令人摸不着頭腦。透明度不足,令坊間不少人都有一個疑問:到底除了樓宇結構安全、居民生活環境以及實際收購業權上的困難之外,背後又是否有其他因素左右市建局的重建計劃?

由上而下、地產商式的更新以外,有何可能性?

小至一個布市場,大至一整個區的重建和規劃,過程繁複冗長、牽涉的因素眾多,但當中我們可以看見,這些重建項目多年來都無法推行真正以人爲本的市區更新。在現行制度下,市民參與整體市區更新以至規劃過程的機會有限,無論是規劃研究、公衆申訴等,市民往往都只是被動的一方,而無法做到真正的與民共議。另一邊箱,作爲公營機構的市建局雖獲《市區重建條例》賦予不少權力,但在財政上需自負盈虧。在此商業運作模式之下,亦難以逼使其將公衆利益放於首位。

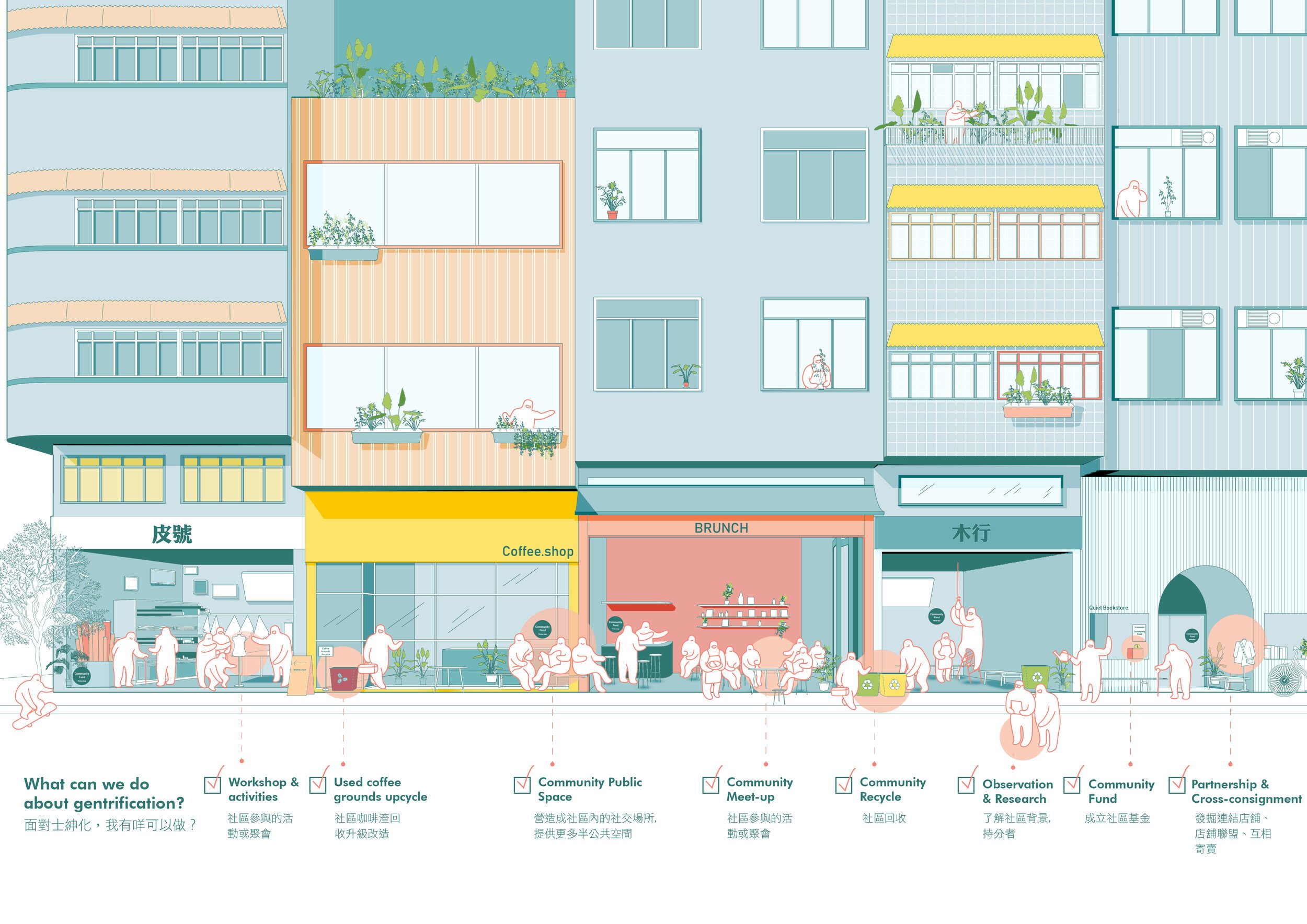

在此困局下,或許可以借鏡英國、加拿大(溫哥華)等地多年行之有效的方法:在現行制度之上,再建立一套積極地與公衆共同規劃,甚至能夠讓市民自行組成規劃聯席,進行規劃研究及公衆諮詢,並提出社區願景(Community Vision)及替代方案的法定社區規劃制度(Neighbourhood Planning),就正如上一篇 GUTS: CASE OVERSEAS 所提到的甘利街社區規劃案例一樣。而縱觀海外各大城市,市區更新都需要政府在不同程度上的參與,尤其是大規模、以街區為單位的項目,許多時都需由政府統籌,聯合各個部門,甚至重新審視現行制度及框架,再加上民間協作的形式推進。誠然,要解決香港現有的困局殊非易事, 亦未必是這系列的文章能夠解答到的,但希望藉著這個專題抛磚引玉,邀請大家一起反思最適合香港的市區更新模式。

GUTS has recently brought forward discussions on the purpose and multi-dimensionality of urban renewal, and debunked the myth that equates urban renewal with redevelopment. Through a number of overseas cases, we also explored how urban renewal should be people-centred to fulfil the primary goals of preserving existing urban fabric and community networks, improve the living conditions for residents of old districts, while responding to residents’ needs. With reference to the recent urban renewal projects in Hong Kong, let’s examine whether urban renewal has really tackled urban decay problems.

The clearance of Pang Jai in Sham Shui Po: What role do community proposals play under the current system?

Commonly known as Pang Jai, the Yen Chow Street Temporary Hawker Bazaar in Sham Shui Po, was permanently closed on 31 January 2023. In 2015, the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) proposed to permanently demolish Pang Jai to make way for public housing development. This was done without any prior public consultation, even though it was the only remaining fabric market in Hong Kong.

Stall owners have been fighting for Pang Jai relentlessly over the past 8 years. Not only did they collaborate with various community organisations to organise different events, such as guided tours, markets and fashion shows in; they also established the Sham Shui Po Market Participatory Planning Platform (the Planning Platform). They hosted two rounds of community planning workshops with many stakeholders and professionals, including urban planners, designers, vendors, customers, Sham Shui Po community groups and residents. While most stall owners hope to stay in Peng Jai, they also explored different relocation options during the workshops. The stall owners also aligned their expectations on basic principles for relocation, such as negotiating for collective relocation and affordable rents. The Planning Platform later came up with a community proposal titled “Pang Jai Community Fabric & Fashion Hub”. Based on FEHD’s plan to relocate Peng Jai to Tung Chau Street Temporary Market, the Planning Platform envisioned the ‘new’ Pang Jai to be a multi-functional community space combining retail, fabric arts, and fashion. The proposal received the Wendy Sarkissian Courage Award from Australia as well as the Silver Award (2017) from the Hong Kong Institute of Planners.

The government, however, remained determined to demolish Pang Jai. Even though the Planning Platform submitted the alternative proposal to the government in June 2016, and held discussions with district councillors and other relevant departments, FEHD made no alterations to the relocation offer, which categorised stall owners into groups according to the licences they held. Critics say doing so divided and discriminated against stall owners. In 2018, the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau (CEDB) announced the plan to build a five-storey design and fashion hub in Tung Chau Street in Sham Shui Po, which aims to “nurture a new generation of design and fashion talents”. In fact, CEDB’s plan shared similar goals with the Planning Platform’s proposal, in particular the provision of common facilities and spaces for fashion and garment manufacturing. However, it neither mentioned a word about the relocation arrangements of Pang Jai nor shared the community vision which the Planning Platform has advocated for. CEDB even stated that its plan, unlike Pang Jai, served different purposes and target groups. Eventually, only 16 out of the 49 “eligible” Pang Jai stall owners accepted FEHD’s relocation offer. The rest of the group and other “ineligible” owners could only choose to accept and leave. It is simply a pity to see bureaucracy stifle the richness of social capital and squander the chance to collaborate with the community.

Housing Authority’s demolition of industrial buildings: Are research reports more important than stakeholders’ voices?

Pang Jai stall owners were not alone in facing redevelopment-led evictions brought by the government. Tenants of factory buildings managed by the Hong Kong Housing Authority (HA) faced similar struggles. In response to the recommendations of the 2019 Policy Address, HA completed a study in 2021 regarding the demolition and redevelopment of its factory estates for public housing. Subsequently, HA announced plans to demolish 4 factory estates—Yip On Factory Estate in Kowloon Bay, Sui Fai Factory Estate in Fo Tan, Wang Cheong Factory Estate in Cheung Sha Wan, and Kwai On Factory Estate in Kwai Chung—which have a high occupancy rate above 97%. Tenants were required to move out by the end of November 2022, and were offered the options of bidding for vacant units in Chun Shing Factory Estate and Hoi Tai Factory Estate, or look for new industrial units in the private sector. Relocation, sadly, was not an easy task for most tenants as their businesses required a huge amount of space for housing heavy machinery. Furthermore, loud noises were inevitably generated during their operations which limited suitable relocation space. Moreover, the relocation and refurbishment works would cost several hundreds of thousands, not to mention the surge in rental prices of private factory buildings after HA announced its plan. A handful of tenants found alternative workspaces, but the overwhelming majority of tenants had to close or sell their businesses.

Like the Pang Jai stall owners, tenants affected by HA’s demolition plan formed a concern group in June 2021 to petition the government to withdraw the plan. They even put forward a compromise proposal of “demolishing three blocks and keeping one block”. Yet, their efforts over 1.5 years ended in vain. Relevant departments did not contact or consult the tenants, and no communication channel was set up. The impact caused is considerable. Demolition not only affected a huge number of tenants; some of them were also major manufacturers and essential suppliers in their fields. Demolition and redevelopment would also upset the inheritance of traditional craftsmanship. If the government had engaged tenants upstream during the planning stage, both parties could have co-developed the resettlement plan and associated support policies to minimise the impact caused.

Redevelopment in To Kwa Wan: What is the value of redevelopment?

Unlike most of the redevelopment cases in Hong Kong, residents of the “13 Streets” in To Kwa Wan have been pressing for redevelopment for years due to safety concerns. In the 1960s, seawater was allegedly mixed in the cement used to construct some buildings. This caused steel reinforcing bars to corrode and subsequently caused the reinforced concrete to crack and spall. Haunted by the building collapse incident at Ma Tau Wai Road in 2010 that caused 4 deaths and 2 injuries, residents of the “13 Streets” were worried about the structural safety of their homes and hoped the government could take the initiative to redevelop the area. But, the Urban Renewal Authority (URA)’s recent redevelopment schemes in To Kwa Wan did not cover the “13 Streets”. When asked about the reason for excluding “13 Streets” and the nearby “5 Streets” area from the plans, Wai Chi Sing, the Managing Director of URA was quoted saying that the acquisition cost, which amounted to 40 billion, was beyond URA’s current financial capacity. According to Wai, the URA had to “save enough money” before commencing redevelopment work, and he urged building owners to be responsible for the repair and maintenance work of their property. However, it was not until months later in December 2022 that URA announced two seaside redevelopment sites, namely Ming Lun Street / Ma Tau Kok Road Development Scheme, which includes the “5 Streets” area between To Kwa Wan and Kai Tak, and To Kwa Wan Road/Ma Tau Kok Road Development Scheme. The two schemes cost over 10 billion. “13 Streets” area was left out again, causing residents to wonder if the URA is prioritising potential profits from the development of prime locations over the urgency to solve residents’ pressing safety and living needs.

What made people more baffled was the fact that a number of structurally sound buildings, and those currently undergoing rehabilitation work or had been rehabilitated within the last 6 years, were included in URA’s redevelopment schemes (For example, see the Kau Pui Lung Road / Chi Kiang Street Development Scheme and To Kwa Wan Road / Wing Kwong Street Development Scheme for more details.) As the redevelopment criteria for these schemes lacked transparency and qualifiable standards, it is questionable what unknown factors, apart from the buildings’ structural safety, residents’ living conditions, and the challenges in acquisition, had influenced URA’s decision-making for redevelopment.

What are the possibilities beyond top-down and developer-led renewal?

Be it a fabric market or a district-level rehabilitation project, the process of urban renewal and planning could be lengthy and complex and often involve a myriad of different considerations. The cases mentioned above highlighted problems arising from the absence of people-centred decision-making and limited public participation. The current decision-making process does not require community consensus, and the public could only play a passive, reactive role throughout the various stages of redevelopment, from research and planning to complaint-handling. On the other hand, despite the vast powers granted by the Urban Renewal Authority Ordinance, URA remains a self-financing statutory body. The decisions it makes reflects its priority to achieve commercial viability more than serving public interests. This poses a challenge in striving for a more people-centred approach to urban renewal.

Perhaps we can look abroad for more innovative solutions. For instance, in Britain and Canada (Vancouver), there are well-established community-based initiatives that facilitate public participation in planning. The public can form their own neighbourhood forum to conduct research and public consultation on redevelopment plans, and submit their proposed community vision and alternative neighbourhood planning policy. The Neighbourhood Plan of the Camley Street Neighbourhood Forum which we introduced in the last GUTS:CASE OVERSEAS article is a perfect example.

In other major overseas cities, urban renewal requires government interventions at various levels, especially for large-scale projects that affect districts. Coordination between government departments and even the re-examination of existing systems and frameworks is necessary to foster collaboration among departments and seek support from community organisations. Redevelopment issues in Hong Kong are too complex and challenging for this series of articles to offer solutions. However, we hope to encourage everyone who cares about the city to put our heads together and give some thoughts on creating an urban renewal system that best serves the needs of Hong Kong.

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: