智慧監獄=智能化?|A Smart Prison

過去一個月,我們看過香港早期蜚聲國際、講求效率的監獄佈局,也看過現今世界上前衛的監獄設計,這對於關心香港未來監獄設計的吉人們來說,又有沒有一點啟示呢?當不少先進國家開始怎樣的監獄設計哲學,才對社會最有用的同時,香港如今最新的發展,又是朝著什麼方向呢?

在談監獄之前,我們可以先看看,香港公共建築近年的設計,其中一個明顯的趨勢是智能化:新建的政府大樓用上慳水慳電、完善廢物處理等的最新科技;舊大樓則按綠色建築標準改裝。而建築方法方面,也用上新技術,例如引入「組裝合成」的方法,預早製成組裝配件後,再經過品質檢查,才付運到現場組裝,不但可以降低工人的人身安全風險,還可以減少建築結構出現問題,竹篙灣檢疫中心,及首個過渡性社會房屋項目南昌220,就是最新近的例子。

而作為公共建築之一,香港的監獄當然也開始了智能化。這除了以打造環保建築為目標,例如節約能源與減少污染之餘,同時也提升監獄的管理效率,正如很多機構一樣,讓智能化減省人手。

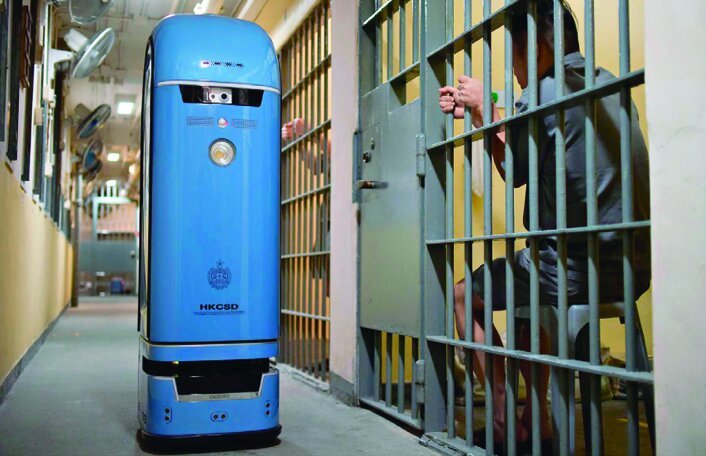

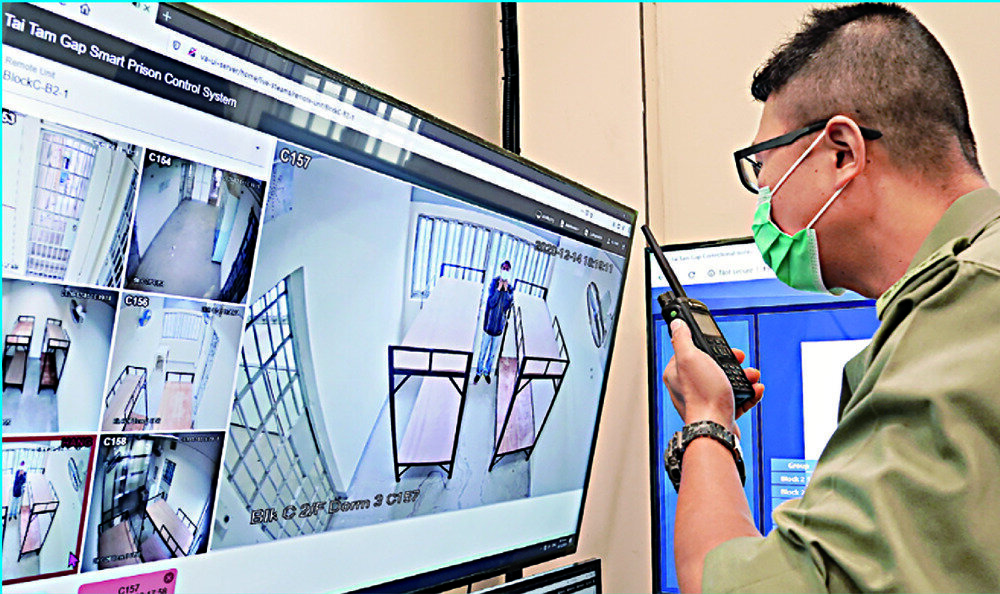

不過,在監獄裏用上智能系統,不論香港抑或其他城巿,都總會引起關於私隱的關注。翻看立法會文件的紀錄,懲教署在2019年展開「智慧監獄」計劃,把人工智能、物聯網及藍芽技術,都應用於加強現今的保安。譬如,壁屋監獄應用的影像分析監察系統,能感應在囚人士中不尋常的行徑,例如虐待及自殘。有關科技正在某些在囚人士本應享受私隱的地方進行試驗,如宿舍及廁所。

羅湖懲教所現正引入另一個裝置,和市面上售賣的智能運動手環相似,可監察被還押人士的生命表徵和他們的實時位置。而和市面上的不同,在囚人士需全天候戴著這些由懲教署發放的手環,以紀錄他們的生物特徵資料——一些被爭議是最敏感的個人資料。然而,懲教署幾乎沒有披露過將怎樣利用這些資料,也沒有透露如何避免收集回來的資料遭濫用。

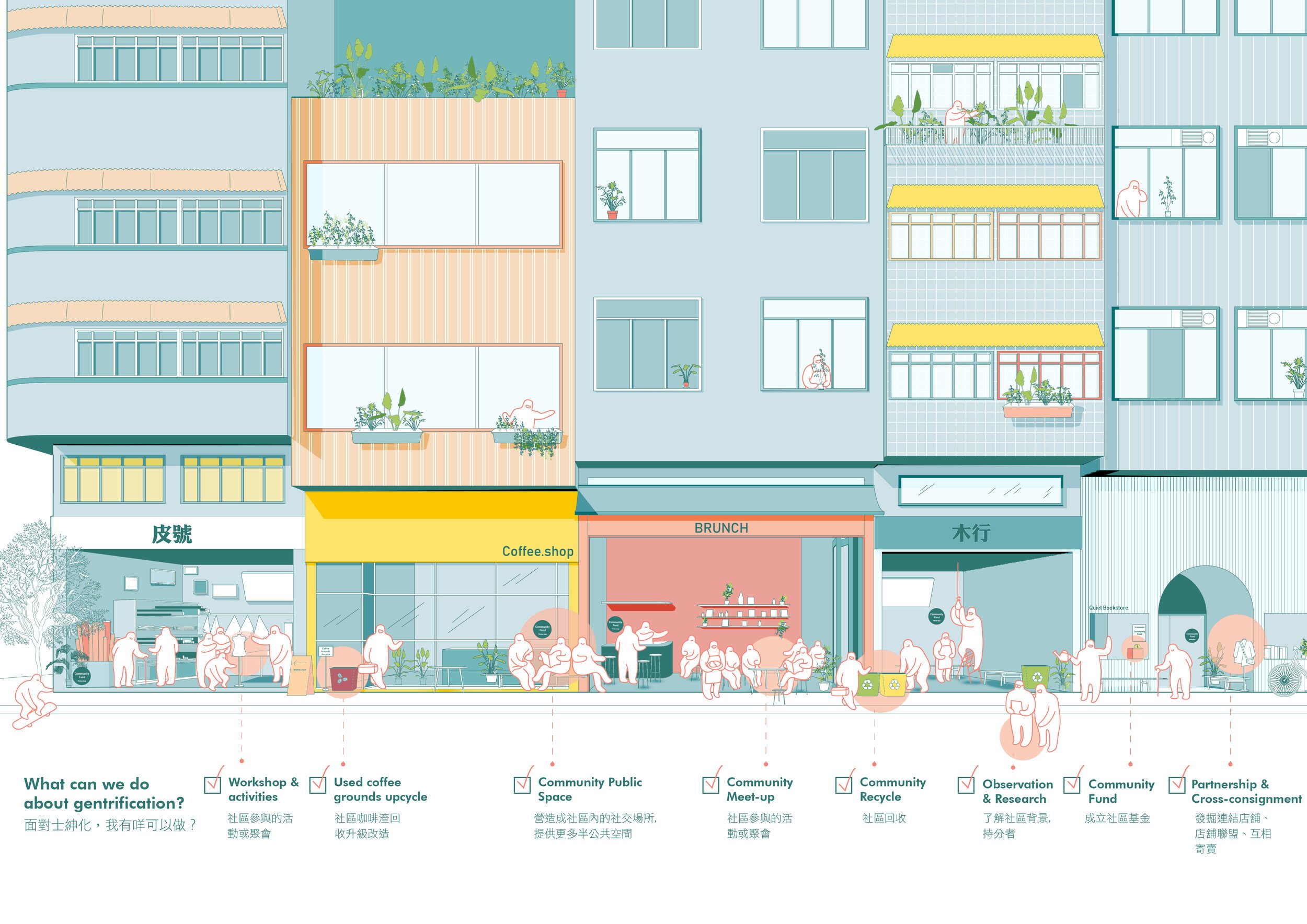

如此看來,正當北歐、美國、新加坡等地方嘗試把監獄建築加入更多人性化設計的同時,香港則更著重其他方向的發展,例如智能技術。當然,不同社會有不同的狀況及需求,不過在科技與人性化之間,大概並不是只能二選一,甚至兩者結合可以發揮更好效果。

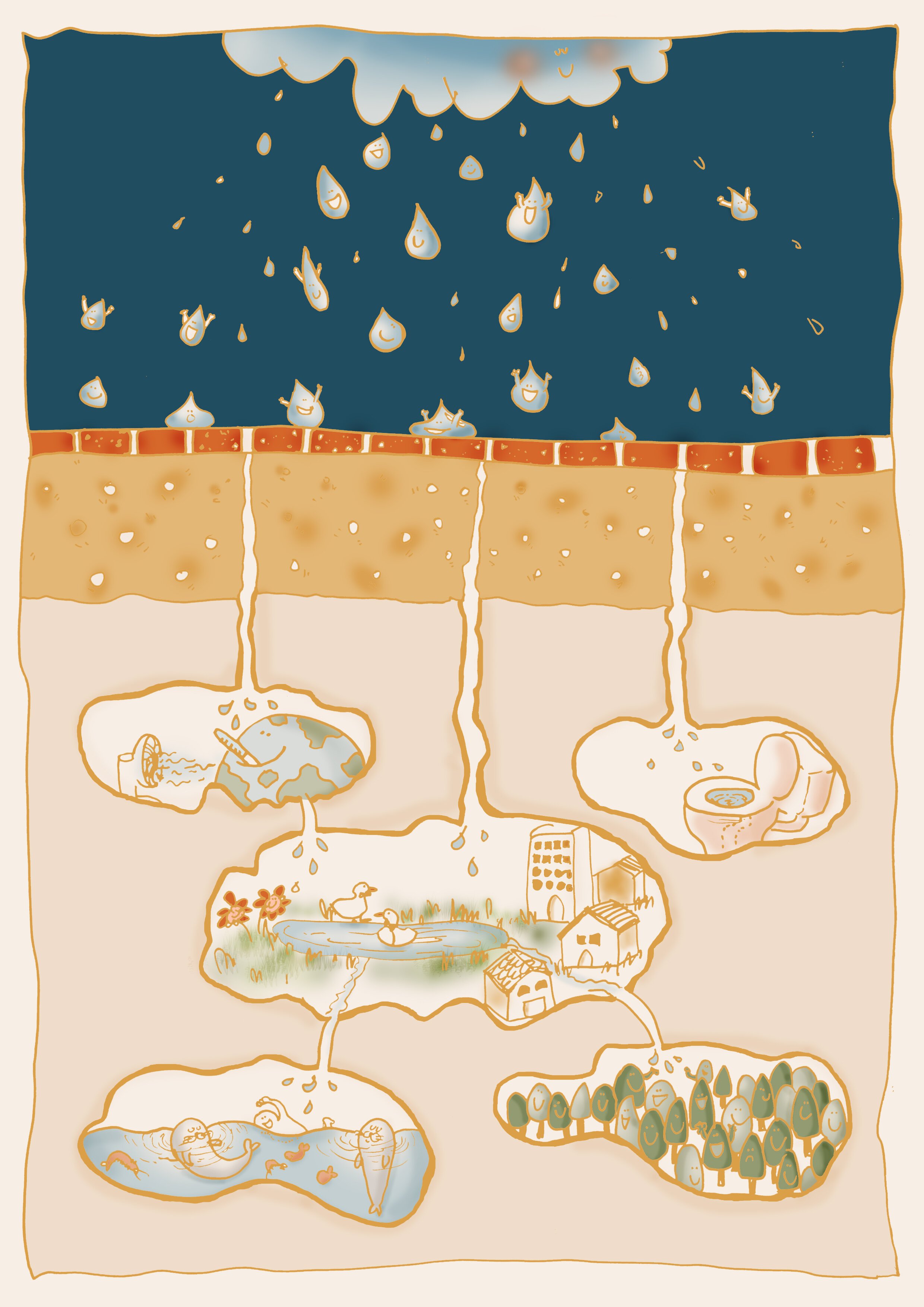

跳出理論框架,我們可以在現實例子裏,看看現今的建築遇上什麼困難、用家有什麼需求,再看看科技是否能幫上忙?近來,最多人討論的,是監獄裏的散熱問題——由於因為香港夏天非常炎熱,而監獄大量運用出名吸熱的混凝土來興建,使監獄酷熱問題更是加劇。就此,科技或許真的可以幫忙改善,例如量度熱舒適性指標。另外,除了科技以外,規劃、設計其實可以大派用場,例如,考慮宿舍的座向,減少在在東方或西方直接面對太陽強光直射的機會,或者降低建築物深度及增加窗口數目,以加強通風。以這些為基礎,再用風機至監獄內部抽走熱空氣,令新鮮空氣得以流通,更可減低空氣傳播疾病的風險。

這令我們想起,香港公屋之父鄔勵德在二次世界大戰時被囚禁在深水埗拘留營,他對那建築物的親身體會,是欠缺通風。戰後,他理解到香港幾乎所有巿區房屋都有這問題,而板間房的問題尤其嚴重。於是,他在公屋單位之間的牆身上設計出鴿巢孔,並在開放式走廊用上通風磚而非實心石屎牆,促進更多氣流通過。

這些第一代公營房屋獨特的設計,象徵了政府對持續改善公共房屋居住環境態度進取,而這些卻是鄔勵德從牢獄中帶出來的領悟。

相片來源:網上圖片

地點 : 香港

GUTS Thoughts | A Smart Prison

For the past one month, GUTS have revisited innovations over the past century that optimised the efficiency of Hong Kong prisons, which made it a renowned leader in penal design. We also showcased cutting-edge practices rolled out in prisons worldwide. Now that we have a sense of both historical and contemporary trends for this moribund building type, it is perhaps time to consider the current trajectory Hong Kong’s prisons are leading towards and how these moves reflect the relationship between the wider society and those incarcerated.

The adoption of smart strategies is an obvious trend for Hong Kong’s public architecture. New government buildings are designed with the latest technologies to conserve energy, water consumption, and optimise waste management, while older ones are retrofitted to meet current conservation standards set by the Green Building Council. Even construction, long considered a laborious and dangerous industry, is getting a smart makeover through modular integrated construction (MiC) technology, cutting down safety risks and reducing the likelihood of building defects since every free-standing module is prefabricated and underwent quality control checks before shipping out for on-site installation. Recent examples include the quarantine centre at Penny’s Bay and Nam Cheong 220, a transitional social housing project.

Prisons Get Smarter

As part of our public architecture, it is inevitable that prisons have to be smarter to keep up with the times. On its website, the Correctional Services Department (CSD) emphasises how environmental protection and food waste reduction measures were introduced at correctional institutions to play its part in conserving resources and minimising pollution. It is not just prison buildings which are getting “smarter”, but also the increasing use of technology to improve operational efficiency and reduce manpower requirements. Surprisingly, the same considerations were documented as far back as the 1850s, and subsequently repeated in the 1920s, as prison authorities paid attention to how building design could improve the operations of Victoria Gaol and Stanley Prison respectively.

Monitoring Prisoners though Technology

Issues regarding the privacy and dignity of those incarcerated have attracted robust public discussion, more so as surveillance becomes more pervasive and invasive ever since the Correctional Services Department (CSD) unveiled its “Smart Prison” concept in 2019. Artificial intelligence, Internet of Things (IoT), and Bluetooth technologies have been engaged to enhance existing security measures. For instance, Pik Uk Prison introduced a smart Video Analytic Monitoring System which detects unusual behaviour amongst those incarcerated in prisons, such as signs of abuse or self-harm. The technology is piloted in spaces where prisoners had traditionally enjoyed some measure of privacy, such as in dormitories and toilets.

Another gadget, liken to fitness tracking wrists sold on the market, was introduced at Lo Wu Correctional Institution to monitor the vital signs of those in custody and track their locations in real time. Unlike their commercial counterparts, those issued by CSD were worn by inmates at all times to record their biometric information, arguably the most sensitive type of personal data. However, not much has been revealed as to how CSD intends to use the data, and the measures in place to safeguard the collected information from potential abuse.

Incorporating Passive Design Strategies

As we saw in the last GUTS CASES article, Nordic countries, the United States, and Singapore have embarked on reforms to make prisons more humane. Whereas Hong Kong has taken a different tack, by emphasising how its prisons have become smarter. The decision to make prisons more humane or smarter is neither dichotomous nor exist at the two extremes of incarceration practices. In fact, why can’t prisons consider merging these two trajectories, by using both traditional and smart technologies to improve the living environment in prisons?

Given the current popularity of human-centred design, prison authorities could perhaps figuratively walk a mile in the prisoners’ shoes to understand their pertinent concerns and immediate “pain points”, before matching the right smart technology to alleviate these shortcomings. A recent issue that had attracted the public’s attention centred on the unbearable heat in prisons, which took on immediacy and urgency especially during Hong Kong’s sweltering summer heat. The problem was also aggravated by the ubiquitous use of concrete in building construction, a material notorious for soaking up heat.

One way to help prisons become more liveable is to consider adopting thermal comfort standards and using both technological-driven solutions and passive design strategies to improve environmental conditions indoors. For example, by reorientating dormitories to reduce exposure to strong sunlight along the east-west axial direction, reducing the depth of buildings, and increasing the number of openings to encourage cross ventilation. Supplementing these strategies with mechanical ventilators to draw out hot air from the interior and encourage the circulation of fresh air will also reduce the risk of spreading air-borne diseases.

Making Prisons Smarter and More Humane

Coincidentally, Hong Kong’s father of public housing, Michael Wright drew inspiration for the design of public housing from the building failures he had observed while imprisoned at Sham Shui Po Internment Camp during World War II. One such problem was a lack of ventilation in urban buildings, a problem further exacerbated by overcrowding and a lack of fresh air and light in partitioned cubicle homes. Wright’s Mark-1 design provided pigeonhole openings in the walls between flats and incorporated ventilation blocks instead of building solid concrete walls along common corridors to facilitate airflow.

These unique features found in first generation housing estates signalled the government’s proactive approach to continuously improve the living conditions in public housing, particularly in efforts to improve air circulation and ventilation. More recently, the Hong Kong Housing Authority has incorporated micro-climate studies and Air Ventilation Assessments as part of the planning and design of new estates.

Now is the right time for Hong Kong prisons to take a leaf from their public housing counterparts. Prison design and operation should not emphasise discipline and regimentation only. Designing empathically from the perspective of those incarcerated will not only make a prison smarter, but definitely also more humane.

Photo source: Internet

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: