香港吉事:天橋底改造有好「橋」?|Hong Kong: Brightening spaces under flyovers

金鐘道至花園道、香港仔至灣仔、公主道至亞皆老街、荃灣至大涌道——這些公路,每天都有上百萬人次,我們靠它們在城巿裏縱橫馳騁,但又有多少人會留意它們何時落成,或者如何建成呢?根據政府資料,香港共有2101公里道路,其中分別有442公里及466公里的路段,分佈在香港島和九龍區的主要市區區域。

另外,香港共有15條主要行車隧道,1340條行車天橋,大部分建於香港經濟起飛及急速工業化的1970至80年代。這一期,我們會首先回顧1950年代早年興建公路的日子,接著將分享一些本地例子,看看它們如何有趣地利用天橋下空間,改作社交、娛樂甚至居住用途。

香港最早期的高架公路

1964年,政府公布香港史上第一條高架公路「花園道交通總匯計劃」,當年本地傳媒大力追捧,有建築雜誌預言6年後、在項目落成之時,中區交通擠塞情況就可以畫上句號。這項工程耗費達1200萬元,被形容為殖民地史上最大型、同時是最全面的道路系統修正,當中包括7條架空公路,沿著海傍位置貫穿夏慤道至中半山區的羅便臣道。由於這是香港首次興建高架公路,跨距的計算及建築應用了二戰後最新工程製作技術。這項技術在隨後數十年間廣泛應用,對於後來香港市區的重建,以及拓展巿區至新界、應付急速增長的住宅及工業需要,至為關鍵。為避免對交通造成阻塞,架空天橋的組件都是預先製成,並只用上短時間在現場組裝。7條高架天橋之中,有一條橫跨了皇后大道東,其橋身用上1464尺的樑,重約900噸,只在一晚之間組裝完成!香港建造架空公路的經驗,成為亞洲最複雜、技術要求最高的城巿建造打下基礎,牽涉的世界知名基建項目,包括1987年的西九龍走廊、1997年的青馬大橋,以及2007年的深圳灣大橋。

毋庸置疑,天橋是促進社會發展的重要基建,不過,它同時在本已有嚴重土地短缺問題的城巿製造大量難以使用的暗黑空間。雖然,香港未出現如上一篇文章所提到、改造天橋底的外國例子,但近年不論政府部門抑或民間團體,也有意識地希望能善用天橋底的空間,以創新的設計解決一些社區需要。這些嘗試,是否都把天橋底空間運用得宜?我們從中又可以得到什麼啟發?

橋底環保站:如何追得上社會需要?

東廊天橋下,原本有一個臨時停車場,如今變成了一個禪味空間——竹枝屏風後,幾個長方形平房佇立,部分綴有落地破璃,引入自然光,但不覺熱力逼人,因位處橋底,避得過陽光直射。平房外設有小園林,越過草地、鵝卵石道,算是一場輕鬆散步。這樣微妙的空間,竟然是個回收站。

有份改造空間的建築師李百怡說,目標不止是興建回收站,而是打造一個公共空間:街坊不是去完回收站、放下物品就要走,這兒是可以停留歇歇,所以建築師才會花心機,將老舊貨櫃變為竹調平房,石屎地變為散步道,營造舒服的氣氛。不止東區,多個「綠在區區」社區環保站,皆選址於未盡其用的地方如天橋底,其他還有「綠在深水埗」、「綠在沙田」等。

不過,由設計到落成,經歷好幾年,香港人的環保意識愈來愈高、廢物回收量愈來愈大,當年設計的設施,時至今日早已不敷應用。除了把空間美化、把建築建好,在運用城巿珍貴空間的時候,我們如何可以更好地規劃、更好地滿足不斷變化的需求?

在橋底解決房屋問題?

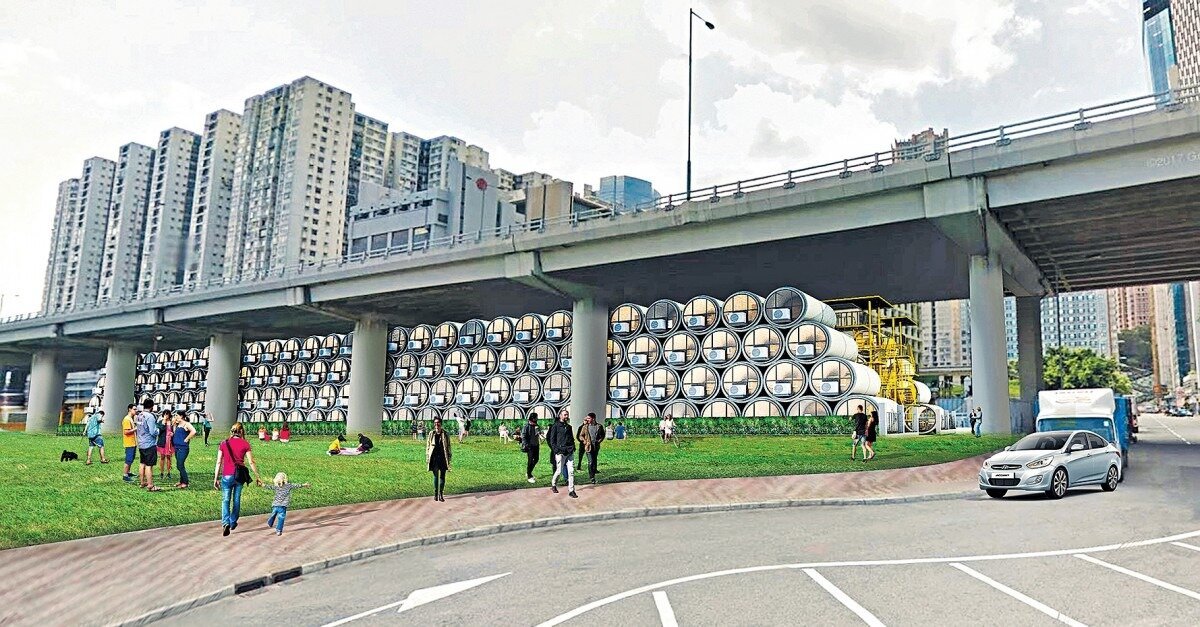

小時候看卡通片《叮噹》,水管空地是常見場景,技安與小夫當了水管是會議室,鑽入裏頭共謀捉弄大雄的計劃。而在香港,水管改裝的房屋確實有機會出現,最初選址的是荃灣海角街及海興路交界、橋底與橋旁的空地。橋底建水管屋,這概念聽上去沒錯很創新,不過,廢氣、嘈音,以及「吓,你住天橋底」的污名,仍是大眾的批評焦點。由此來看,橋底建屋還有幾層關卡。

水管屋(OPod)的靈感出自建築師羅發禮,2018年落入民間討論。混凝土水管成本低,能夠防火隔熱,興建規模有彈性,可多可少,需時比傳統建樓為短。每個單位約100平方呎,供1至2人居住,有基本的廁廚設施。仁濟醫院就此推出「社會房屋試驗計劃」,以興建水管屋、短租給基層市民為目標,選址修訂為橋旁的空地。

如果,香港土地嚴重短缺、而城中的橋底空間又太多,它是否可以用來解決最急切的房屋問題?所謂住屋需求,我們應該如何平衡量與質?

橋底,也可以是活潑的社區空間

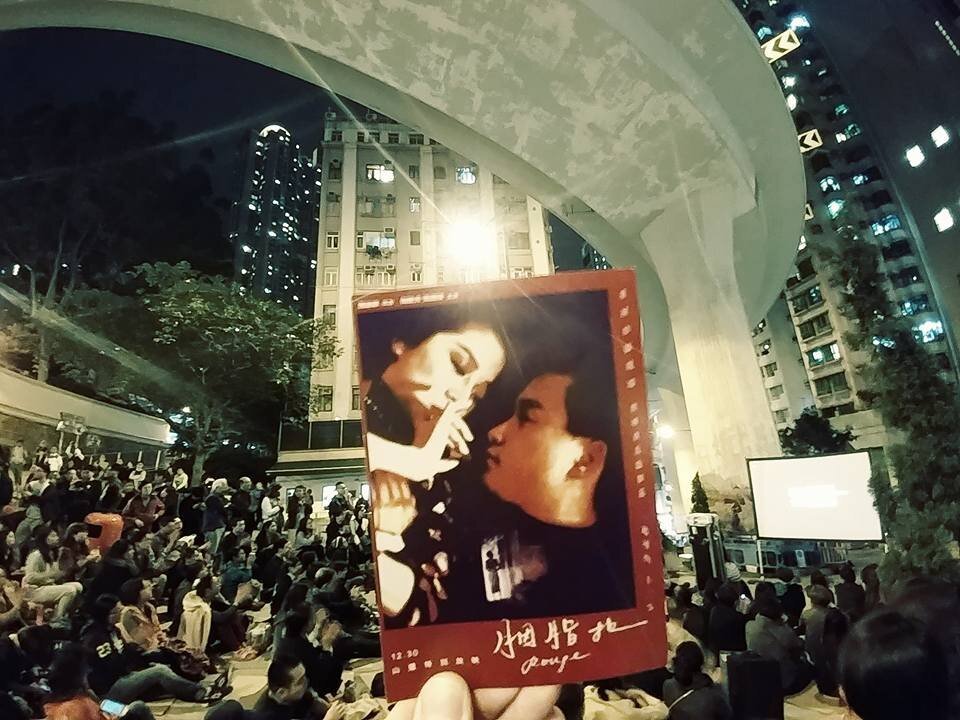

山道的S形天橋,是西區其中一個最為人所知的地標,S形天橋的兩邊貼近樓宇,坐在巴士之上有如坐過山車,是不少乘客的回憶。而高橋底下的遮蔭大斜路,則是香港難得一見、生氣勃勃的社區空間。

這裏辦過不少奇趣的社區活動,例如盂蘭節設臨時戲棚,上演神功戲;丹麥設計師帶木工工具上陣,教街坊手製北歐家俬,居民則回贈羊腩煲,橋下齊齊開餐。有本地社企曾辦「留有餘地」社區空間營造計劃,邀請居民參加墟市擺檔,學生幫手改裝車胎為貨物桌,解決斜路擺貨的困難。籌備過程中,區內車行捐廢棄車胎、裝修店借出工具、街坊經過停下幫忙等,拼砌出共同經歷。時至今日,西區墟市還不時舉辦,山道下仍見人氣。

在壁畫以外,橋底藝術有其他可能性?

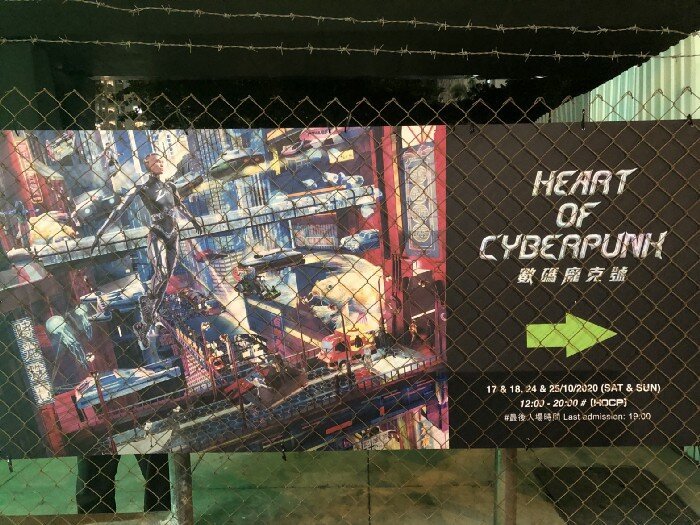

隱蔽又幽暗的橋底,每當要美化、改善,十居其九都是在橋躉之上畫壁畫。以藝術介入橋底,在外國不是新鮮事,而在去年,香港深水埗也嘗試跳出壁畫框架,舉辦以Cyberpunk 為主題的時裝展覽及創意市集數碼龐克號。

雖然吸引不少人參與,卻同時引來爭議。橋底過往有不少無家者露宿,附近一帶近年有不少新住宅大廈落成,而巿建局的重建項目也近在咫尺。由於地理位置敏感複雜,不少人認為這個展覽促使政府「清場」趕走無家者,同時因為巿建局重建項目將開設5層設計及時裝基地,而經營權亦交給橋底展覽的主辦單位,引來很多批評的聲音。

主辦單位及後多次澄清,而這讓關注舊區活化的人也上了一課:社區營造,不止需要獲得公共空間的使用權,還需要好好處理原本的社區關係,獲得社區的認同。雖然碰壁,但這場展覽看來是很好的切入點,探索橋底與藝術的可能性。

地點:香港

圖片:網上資料、西環變幻時、娛記正傳

Queensway -Garden Road, Aberdeen -Wan Chai, Princess Margaret Road –Argyle Street, and Tsuen Wan-Tai Chung Road. These are familiar names Hong Kong commuters familiar with, as millions criss-crossed the city on these major highways daily. These elevated roads have become such an integral part of urban infrastructure, not many have given a thought how and when they were constructed. According to government data, there are 2,101 km of roads in the territory, with 442 km and 466km of them weaving through the main urban areas of Hong Kong and Kowloon respectively. There are also 15 major road tunnels, and 1,340 flyovers, the majority constructed were during Hong Kong’s economic boom and rapid industrialisation of the 1970s –80s. For this GUTS: THOUGHT, we will bring you through the early days of highway construction in the 1950s before showcasing some interesting spaces under flyovers that have been adapted for social, recreational, and even residential purposes.

The earliest flyovers in Hong Kong

The announcement of the “Garden Road Complex” in 1964 was met with much fanfare in Hong Kong’s media, with an architectural magazine heralding the completion in six years’ time as the solution for a lasting “goodbye to Central District Congestion”. The $12m development was described as the biggest and most comprehensive road system overhaul in the colony, comprising seven flyovers that would provide seamless travel between Harcourt Road along the waterfront to Robinson Road on Mid-levels.

The bridge spans of flyovers were constructed in pre-stressed and pre-cast reinforced concrete, a new form of engineering and fabrication technology that was introduced after World War II. Its prevalent use in the ensuing decades bore testament to Hong Kong’s urban renewal and its expansion efforts into the New Territories to meet growing demands for residential and industrial facilities. To minimise disruption to traffic, bridge components were made offsite and assembled on-site within a short period of time. One of the seven flyovers spanning over Queen’s Road East, which comprised fourteen 64 feet beams weighing around 900 tons, was assembled within one night! Hong Kong’s experience in building flyovers laid the foundation for the city to realise of Asia’s most elaborate and technically challenging infrastructure projects, including the West Kowloon Corridor in 1987, the Tsing Ma Bridge in 1997, and the Shenzhen Bay Bridge in 2007.

We cannot deny that Hong Kong has advanced through these infrastructures, however, the accumulation of unused underside spaces is also alarming when we are facing land shortage. Are there no solution to spaces under flyovers? What are the trials that could give us some insights and lessons learned?

The community green station - how to grow with the rising green demand?

The space beneath the flyover of the Island Eastern Corridor was previously used as a temporary car park – a common use for such leftover spaces. However, using just a few modified container modules, some cladded with rows of reused bamboo arranged aesthetically as screens and frames and others with the outer steel skins replaced with floor-to-ceiling glass panels to illuminate the interior space with natural sunlight, the Architecture Services Department (ArchSD) has successfully transformed this neglected space into one infused Zen qualities. Coupled with other outdoor facilities such as courtyards, lawns, and stone paths, the atmosphere here is tranquil and comfortable, no doubt enhanced by the shade provided by the flyover sheltering the space.

The fact that such an inviting space is used as a recycling station, demonstrates the effort government departments invested to rehabilitate spaces under flyover which are usually neglected and piled with rubbish. Instead, they could be brimming with potential for community activation given the right opportunities. The Eastern Community Green Station (CGS), or Green@Eastern is one of the seven CGS built by the Environment Bureau across the territory under the initiative Green@Community. These CGSs are designed with clean and bright interiors and attractive facades to improve the general public’s receptiveness towards recycling. Even the locations were well thought out. Apart from utilising spaces beneath flyovers, CGSs could also be found in parks, rest gardens, and within public housing estates.

Li Pak-yee, a Senior Architect with ArchSD found her contribution to Green@Eastern’s revitalisation rewarding and meaningful. “The goal was not to build yet another recycling centre, but to also create an inviting public space,” she recounted. “We do not want kaifongs to just visit the centre to drop off items for recycling. Instead, we hope they would also relax here.” To achieve this seemingly simple aim, Li and her team spent lots of effort to refurbish old containers to create timber cladded interiors designed in warm natural hues and incorporated a number of courtyards and stone paths to create a calm soothing atmosphere.

The demand of recycling has been growing in the past decade. Better functional support and a stronger identity will be the next challenge so that the space can be fully enjoyed and be part of the public education in green behaviour. Perhaps it’s time for a level up and holistic planning?

Flyovers as an answer to housing shortage?

Fans of the Doraemon cartoon series would be familiar with the rows of concrete water tubes at one corner of the playground where the eponymous robot cat and his friends often hanged out. The pyramidal shape of stacked up water tubes, which provided many hidden nooks and corners, served as Giant and Suneo’s “fortress” to plot devious pranks on the hapless Nobita. In Hong Kong, the dream of living in such a fortress could soon become a reality. An empty plot in Tsuen Wan, located at under the flyover at the intersection of Hai Kok and Hoi Hing Streets, has been selected for this OPod pilot project spearheaded by Hong Kong-based architectural firm James Law Cybertecture. While many have praised the innovative concept of converting concrete water tubes into living spaces, critics have also weighed in. They cited noxious fumes, loud noises, and above all, the stigma of “rough sleeping” under the bridge, as key reasons against OPod’s implementation. It is apparent that the problems associated with living under the flyover are not simply technical or logistical. They also involved complex social and physiological impediments that must be resolved.

To do so, Law has been conducting public outreach and discussions for his OPod scheme since 2018. He hopes this brainchild could address some shortcomings in Hong Kong’s housing situation. For instance, the base material - concrete water tubes are not costly and have good fire insulation properties. The tubular shape offers flexibility in construction planning, allowing for different permutations and stacking arrangements to meet different development requirements. The construction time could also be reduced since the tubes are prefabricated and the interior fitting out of each module, which provides about 100 square feet of living space for a single or couple, could be done more speedily than conventional renovation works. Law has also partnered Yan Chai Hospital to launch the Transitional Housing Project, using the vacant plot next to Tsuen Wan flyover to offer short-term rental of these water tube homes to needy residents.

A seemingly perfect formula if this proposal works. However, the balance of quantity and quality is still a question mark being left behind. How to achieve a healthy living space rather than a shelter? Perhaps there will be more experiments and creativity from professionals needed.

Many activities in one space is the answer?

The S-shaped flyover over Hill Road is a well-known and distinctive landmark in the Western District. Like a coiling snake, it winds between two rows of tonglaus and residential towers, creating hairpin turns that made every bus ride on the flyover a rollercoaster experience. Unlike most spaces beneath flyovers which block out sunlight and give off creepy vibes, the slender width and tall height of this Hill Road flyover creates a brightly lit and yet sheltered slope that has become a popular community node.

Interesting activities happen all year round on Hill Road. For example, a bamboo theatre is erected annually during the Lunar Seventh Month, also known colloquially as the Ghost Month. As the name suggests, opera performances are put up in that month for spirits visiting our realm when the gates to the netherworld open. Occasionally, one could find a Danish designer bring his carpentry tools to a rest garden under the flyover, teaching kaifongs how to make wooden furniture. In return, friendly residents brought him home-cooked dishes such as lamb stew. Such informal making sessions would end with a potluck and a promise to gather again, which helped sustain and strengthen community ties. A local NGO was also inspired by the closely knitted community and initiated a placemaking programme to beautify Hill Road and activate it on weekends through bazaars. Residents displayed goods for sale on tables made from used tyres donated by car repair garages in the vicinity. Students from neighbouring schools were also invited to design and paint these tyres on site. These weekend activities attracted residents passing by and they too were invited to participate in this communal gathering. Placemaking is like a positive feedback loop. The more interactions there are, the more shared memories created, which thereby contribute accumulatively to Hill Road’s vibrancy and popularity as a community node under the flyover.

Are we running out of artsy juice apart from mural art?

We have seen more and more mural art on the columns of the flyovers. Is this already the maximum potential?

Last year, the space under the Tung Chau Street flyover played host to a Cyberpunk fashion exhibition and creative bazaar. The event tried a creative approach and successfully attracted a high number of visitors though its execution has attracted some controversies.

For instance, the space had long been home to a group of rough sleepers. Their ranks have grown in recent years with new upmarket high-rise residential developments and URA’s revitalisation projects in Sham Shui Po driving up rental prices and evicting individuals and families from low-cost subdivided apartment units. As Sham Shui Po has traditionally been considered a district that sheltered the poorest in Hong Kong’s society, the exclusive exhibition became a flashpoint for dissent and disagreements on Hong Kong’s wealth disparity issues. The organisation behind the exhibition was also painted as callous for driving away rough sleepers under the bridge, and a conspirator to the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)’s project to adaptively reuse old buildings in the district to create a design and fashion innovation hub, which will be operated by the same organisation.

This incident serves as a good reflection on the role of placemaking. A successful place activation not only has to cater to its intended audience. It should also seek to create resonance among kaifongs to enhance, rather than disseminate existing community ties.

There are too many solutions that we haven’t tried and experimented before knowing how the spaces under flyovers can be brightened. For all GUTS: Man, time to roll up your sleeves again!

Location: Hong Kong

Image: Internet

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: