歐盟吉事:規劃海洋空間 海洋更健康 產業更穩健|GUTS IN EUROPE: Marine spatial planning for a healthy ocean and robust industry

我們的地球,72%面積為海洋——或許因為相比陸地,大海的浩瀚令我們一直沒有意識到,海洋空間亦被各種人類活動重疊利用,捕魚、交通運輸、油氣資源開採、海上休閒活動、大規模填海,不止人類與海洋生物爭奪資源,產業之間也爭相佔用海洋空間,令海洋生態系統急速敗壞。如果,海洋空間如陸地一樣並非用之不盡,我們有否想過,為海洋空間做長遠規劃?

其實早在2006年,聯合國教科文組織(UNESCO)提出海洋空間規劃(Marine Spatial Planning,MSP)的概念,嘗試讓各國之間協商、建立制度,透過理解海上行業的性質、地域性,把海域分區規劃、把使用權分配給不同持分者。

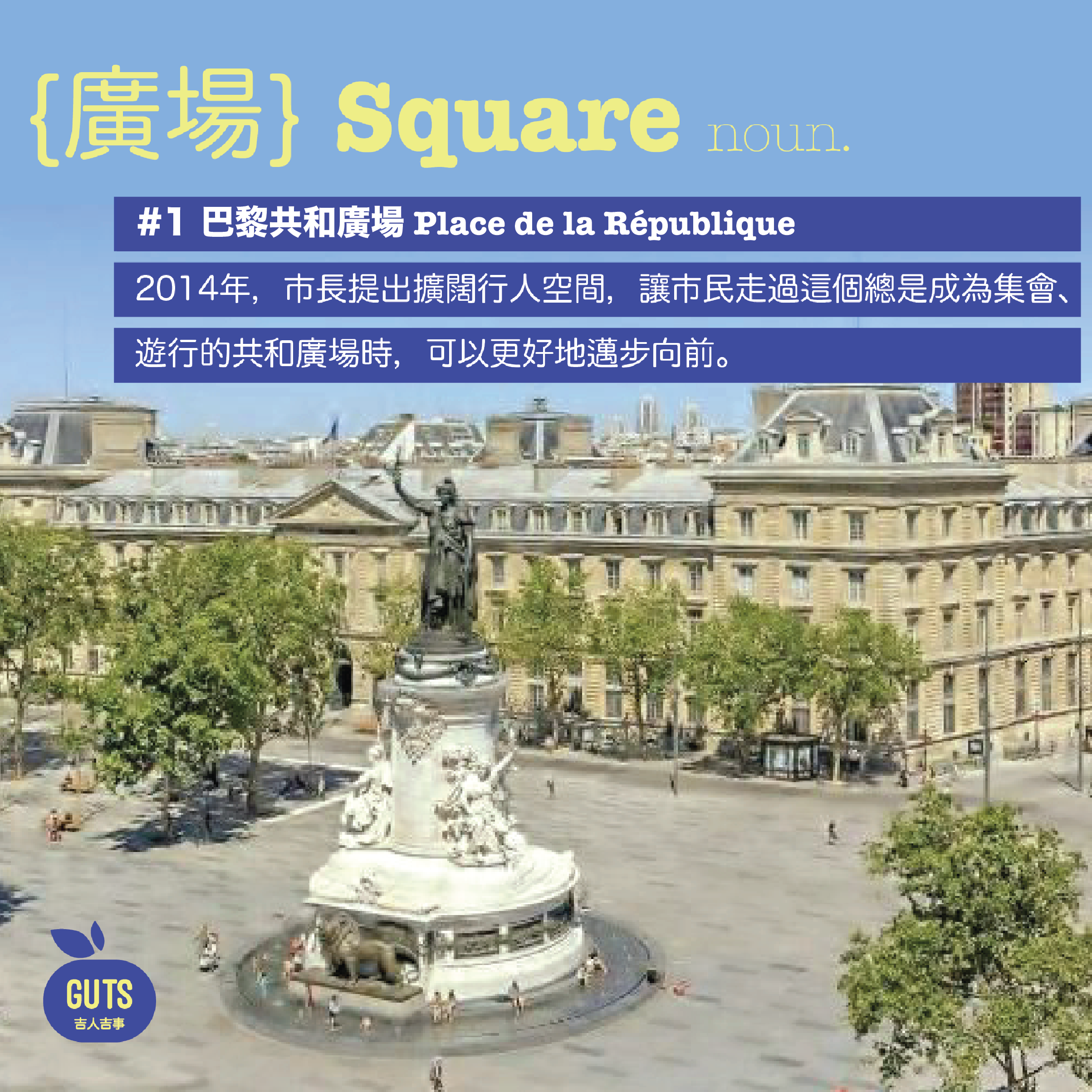

概念提出之後,歐盟是其中一個最先開始規劃的地區,先研究區內海洋產業的特質、運作,當中,歐盟觀察到某些產業之間在使用海洋空間上出現衝突,例如在克羅地亞的札達爾縣,雖然魚類養殖業發展已久,但新興的近岸貝類養殖業,則引來沿岸旅遊業的不滿。除了因為養殖場發出氣味、影響海水水質,它也佔用了原本旅遊業的空間資源,例如使用沿岸步道把漁獲運上貨船。

離岸發電產業,也經常與其他產業出現矛盾。例如比利時與荷蘭,就曾經在附近海域發展離岸風力發電時,因為減少了貨運可航行的空間、減低了運輸效率,而引起了與船運業的磨擦。這個原本在發展風力發電前做好規劃可避免的難題,最後的解決方法是兩國共同組成了一個顧問小組,成員包括公共機構、碼頭、貨輪營運商、船運工會、風力發電場發展商等,重新協定船運路線、可行的安全措施等。

要緩解產業之間的空間爭奪,事前規劃是最好的方法,但這難度不低,尤其要政府部門、甚至跨國政府之間的協調、包容和遠見,而且還需要一點創意。在西班牙,海產養殖與沿岸旅遊使用的空間也重疊,當地發展出一個獨特又創新的方法,把兩者融合、共享空間:在離岸約4公里的海域,養殖場把約500條藍鰭吞拿魚放進海中的大籠,但它同時發展為旅遊景點,在認識相關漁業歷史、購買吞拿魚產品之餘,讓遊客可以機會與藍鰭吞拿魚近距離暢泳,把消費、知識結合真實體驗。

全球的海洋空間規劃發展速度迅速,在提出之初的2006年,當時僅3個國家有擬定的海洋空間計劃,牽涉的海洋面積僅佔各國海洋專屬經濟區的0.3%。時至2017年,已增至13個國家進行規劃,總面積也增至7%。在大趨勢之下,香港在這領域相對落後,吉人不妨從帶起業界、坊間討論開始,把海洋空間規劃的概念帶進香港,讓香港的海洋,能保持最好的狀態,更好地發揮所長。

相片來源:網上圖片

地點 : 歐洲,香港

Oceans occupy 72% of our planet, but such a scale didn't help awaken us to the rooted issues of anthropogenic exploitation. Fishing, transportation, natural resource extraction, marine leisure and large-scale reclamation are some of the human activities by which we compete with marine lives for resources. At the same time, inter-industrial rivalries further deteriorate ocean ecosystems. As we live with finite ocean space, shouldn't we start thinking about long-term marine spatial planning?

Back in 2006, UNESCO proposed the idea of 'Marine Spatial Planning' as a common ground for countries to establish systems for proper marine space zoning, dividing usage rights between stakeholders based on a thorough understanding of the nature and regionality of maritime industries. EU took the lead by researching the characteristics and operations of marine sectors within the region. And, of course, inter-industrial disputes over marine space were observed. For instance, in Croatia's Zadar, the emergence of coastal shellfish farms was met by objections from coastal tourism operators – despite the country’s long history of aquaculture. Besides the odour released from these farms and their adverse impacts on water quality, the tourism industry argued that their spatial resources were exploited, including coastal trails that became docks of cargo ships offloading fish harvests.

Offshore energy industries often find themselves in conflict with other industries. Belgium and the Netherlands tried to develop offshore wind power farms in nearby waters but ended up in disputes with the shipping industry because of shrunk navigable space and lowered transportation efficiency. The dilemma could have been solved by better pre-planning, but it lingered until a joint advisory group was formed to gather representatives from the public sector, pier, freighter operators, freighter unions and wind power farms to re-establish shipping routes, feasible safety measures among others.

While pre-planning is one of the best ways to alleviate inter-industrial tension over space, this solution does come with challenges. It requires institutional, if not inter-governmental, coordination, tolerance and foresight, and beyond that, a sprinkle of creativity. In Spain, spatial overlap between mariculture and coastal tourism prompted the government to combine the two industries in a unique, innovative way. In the area about 4km from the shore, marine farms would place about 500 bluefin tunas in a large sea cage, which has become a tourist attraction, where visitors can learn about the local fishery history, buy tuna products, or even swim right next to the bluefin tunas—an unique authentic experience combining consumption and knowledge.

The global marine spatial planning is developing rapidly. When the idea was first proposed in 2006, only 3 countries penned such plans for only a small marine area that accounted for only 0.3% of their maritime exclusive economic zone. As of 2017, the number of involved countries rose to 13, and the total area also increased to 7%.

Hong Kong is falling behind in this global race. To familiarise the city with this concept, perhaps our first step should be engaging marine industries and the general public in a discussion that hopefully could maintain our maritime prominence and potential.

Photo source: Internet

Location: Europe, Hong Kong

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: