盧樂謙:香港士紳化 文藝背後有元兇|Conversation with Him Lo: The invisible culprit of Hong Kong gentrification

從深水埗站向海的方向走,越過鴨寮街的電子零件檔販、基隆街的布匹檔販,眼前的街道有點不一樣:地舖從批發逐漸換成零售,精心設計過的門面,仿紅磚的皮革店、仿木的咖啡店、仿草牆的外國生果店,一間接一間。「數個月前,我在大南街辦展覽,來看展覽的人在街上排隊,旁邊有個執紙皮的婆婆推著車經過——」新舊交集,文青與老街坊共處所形成的對比,究竟是有趣抑或格格不入?深水埗士紳化的討論,最近又熱熾起來,文藝小店成了被批判的對象。不過,關心社區轉變、近年投入社區營造的藝術家盧樂謙(Him)認為,政府和財團有權力擁有土地的人才是元兇,不能夠只着眼當下眼前見到的咖啡店及文青小店。

屬於80後的阿謙,很早就對社區生活有一種感知。「我在赤柱監獄出生 —— 父親是懲教處職員,一直住在監獄的宿舍。後來父親在我9歲時突然去世,我們就開始了常常搬家的生活。」勵德邨、何文田、長沙灣、北角、太古城,「到中學的時候,我發現自己並不太認同這地方的生活,例如我很需要小餐廳、五金舖,但太古城沒有這類店舖」。會考過後,阿謙在設計學院讀藝術,「那時我自己搬到三家村住,從西灣河搭船去,是間村屋,只得一隻窗」,後來又住過油麻地、筲箕灣等,才開始覺得自己真正活在社區之中。

因為父親猝逝,阿謙一直思考存在的意義,結果在藝術創作中,他找到表達的方法。比起作品,他認為這種經驗更重要,「如果可以讓更多人有這種體驗就好了」。於是,阿謙開始做社區藝術,希望以藝術介入社區,為社區帶來改變。他作了不少嘗試,2012年投入社區營造,出任灣仔藍屋的香港故事館館長;2013年,在觀塘物華街小販巿場清拆時,也嘗試以藝術連繫社區,把保育聲音透過媒體帶出觀塘。

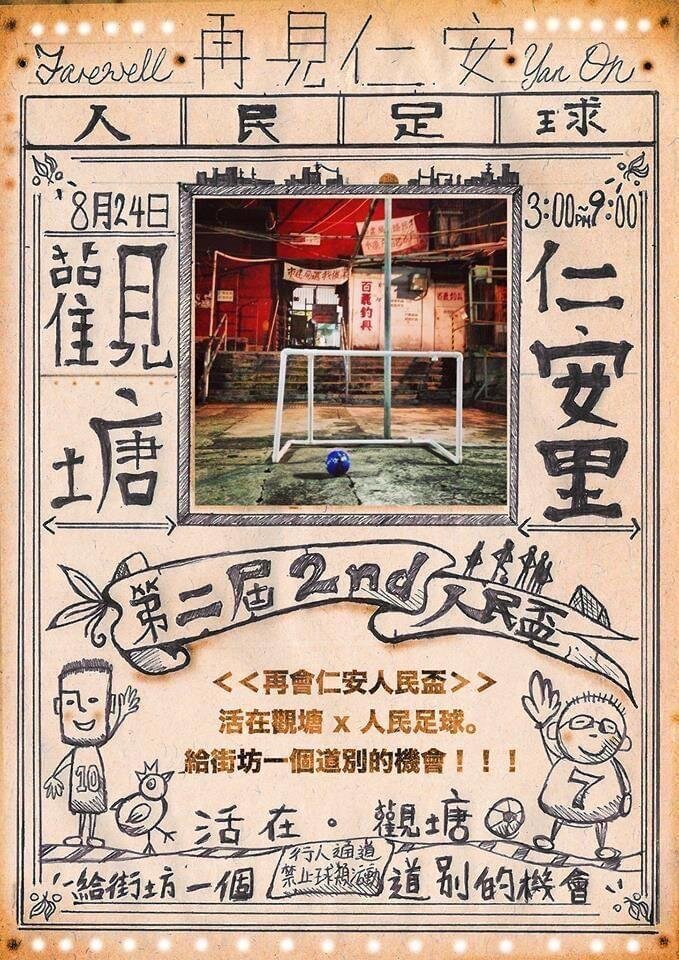

「我和關注保育的朋友到觀塘,聽街坊和小販的想法。」物華街小販巿場裏,有日常用品的檔販之外,也有糖水店、打鐵店、賽鴿店。「我們經常一邊踢波一邊傾,然後有一天,發現平常熱鬧的糖水舖都變得凋零,於是我們在那空地搞踢波活動,用膠水管做了一個龍門」。除了把街坊聚腳的公共空間轉化為「足球場」,我知道這裏有賽鴿歷史,於是我便與街坊一同設計,再找來打鐵店打造一個大型鴿子雕塑,置於將要清拆的天台。「政府部門慣常在晚上才來拆樓,有鴿雕塑坐鎮,他們來拆時至少會有更大動作,讓街坊知道殺到來了。」

在那數年,舊區保育是個熱門話題,清拆重建區區都有,阿謙工作的香港故事館所在地於仔,自2007年利東街大規模清拆重建之後,藍屋成為灣仔另一個舊區活化的重點項目。社工做了很多地區工作,而Him與一班同事及街坊在這些平台之中關注社區文化議題,一同進行地區歷史文化研究,也試過邀請工藝師傅、有機農夫等舉辦工作坊,分享傳統手藝與生活文化,鼓勵公眾與居民參與地區文化的保育討論。Him說雖然社會關注歷史建築的活化項目是否也會否帶來士紳化,從而吸引地產商投資,掀起另一輪重建,但他在灣仔藍屋石水渠街那4年附近街區,並沒有太大翻天覆地的變化,要改變的一早已變了。「是有一兩間酒吧開了,但此後沒有帶動大規模的改頭換面,始終石水渠街一帶比較在灣仔中心的外圍,有些車房結業了,不過他們不見得是因為士紳化而離開,行業式微也有關係。」

多年來獲邀出席講座、分享會談及士紳化,阿謙說在討論之前,先要搞清楚什麼是「士紳化」—— Cafe、酒吧遷入舊區,就是士紳化?如果我們沿1964年首先提出「士紳化」的英國社會學家Ruth Glass所形容的,在城市舊區更新的過程中,趕走舊貧窮、年老或少數族裔等弱勢社群,換來社經條件比較優越的「中產」人口;那麼,我們要看的,就不能只是新開的Cafe、文青小店,「而是他們開店的動機、運作方法,但我們都知道,這些小店不少都沒有那種動機」,有沒有抬高租金、地價的初衷。至於文藝與士紳化的關連,作為藝術家的Him認為,「藝術文化」成了一種符號被商品化,有提升價值的效果,往往就成為一種包裝、賺錢的工具。

以深水埗為例,在2016年掀起士紳化的討論之前,已有藝術家在反對巿建局在深水埗的重建計劃。2013年,有藝術家在「深港城巿/建築雙城雙年展」的開幕禮上,抗議九龍東重建計劃被逐離場。「所以要搞清楚的是,在文藝被說成是士紳化的元兇之前,政府和巿建局早就規劃了重建。」租金樓價被抬頭、社區網絡被瓦解,推手往往是擁有龐大資源的政府與發展商。

放眼整個社區,城巿背後的操作,阿謙用同樣的方式,觀看南豐紗廠 (The Mills)的活化項目,當中亦有文化藝術項目,有否為荃灣帶來士紳化。「要看的是,在The Mills出現前後,周邊的工廠大廈,有否申請改變土地用途。不再如往時賺錢的工廈,會否因為The Mills的出現,而相繼轉型、造成大規模的土地改變?就此,雖然現在看不出The Mills附近有這樣的改變,但需要持續觀察。這亦與政府規劃社區發展的政策有沒有牽涉到相關地區有很大的影響。」

他認為,城市發展,由原本最初一片土地,發展成農地,到現在不斷不斷的由農地發展成為城市,我們看到轉變不停發生,要釐清「轉變」與「士紳化」之間的關係。如果在大家有共識底下轉變,那樣就要先搞清楚有那些大家(持份者)在這個討論過程中參與。「如果一個地方,如果當時所有居民其實都想離開、透過由下而上的討論,而得出再發展的意願,基於這個情況底下發展商成為其中一個持份者,那麼其實重建並不是由上而下的發生。它的邪惡在於由上而下,居民沒有選擇;而如果全香港的重建項目手法一樣、重建出的住宅也類似,最後不喜歡這種新社區的巿民,也變得沒有選擇了。」

那麼,沒有龐大資源的平民,面對社區轉變,有什麼可以做?「不喜歡的話,就先組織區內街坊共同商議,所以社區內自發的民間組織十分重要。正如區內有酒吧出現,你覺得它擾人清夢,就一同去討論,尋找發聲的方法。運用區內的力量投訴吧,如沒有組織,自己就成為發起人,去貼街招,做一個人都做到的事情。」

相片來源:zoom.in.hongkong 、盧樂謙

地點 : 香港

Sham Shui Po is undergoing a rapid transformation, with nicely furnished café, leather shop with faux brick walls, and retailers selling expensive imported fruits carve up the once humble streetscape. When the community is no longer anchored by the old geeky Apliu Street and the iconic garment stalls of Ki Lung Street, does it make life more interesting or challenging? As the debate intensifies on whether cultural industry is the driving force of Sham Shui Po’s gentrification, local artist Him Lo reminds us to look beneath the surface.

With a unique upbringing that was marked by numerous relocations at different parts of Hong Kong, Him Lo, a post-80 artist, has a special perception on community life. “I was born in the Stanley Prison, as my father worked for the Correctional Services Department and we used to live in the staff quarters. When I lost my father when I was 9, I started a life that constantly on the move.’ He has lived in plenty of places, such as Lai Tak Tsuen, Ho Man Tin, Cheung Sha Wan, North Point, and Taikoo. “When I was in secondary school, I realised that I don’t feel a sense of belonging at Taikoo. I needed small local restaurants, hardware shops and I couldn’t find it there.” After completing the Hong Kong Certificate Examination, Him enrolled for an Art major at a design school. “I moved to Sam Ka Tsuen, a village house with only 1 window.” Him’s life on the move had not stopped there, moving to Yau Ma Tei and eventually Shau Kei Wan, where he finally found himself settling within a community.

The lost of his father has made him constantly pondering upon the concept of human existence, of which he eventually found a way to expressed his feelings through art. Him believes that letting the community feels like being a part of something is much more important than any tangible works themselves, which points him to the field of community art. From 2012 onwards, he has been involved in various space making projects by taking up the curator role in the Hong Kong House of Stories in Wan Chai Blue House. In 2013, in face of the demolition of the Temporary Hawker Bazaar of Mut Wah Street, Him again took initiative in an attempt to connect people and the community with arts, but more importantly to give a voice for the need of preservation for the redevelopment project.

“I went to Kwun Tong with a group of friends who were concerned about the topic of conservation in Hong Kong, we wanted to listen to the people and the hawkers.” Inside Mut Wah Street Temporary Hawker Bazaar, you could find all kinds of stores selling household products, desserts, metal work and with some, even organising pigeon racing. “We chat, and we play football together. One day, we find that the once packed dessert store was becoming deserted, so we have a wild thought to DIY a football goal post out of plastic pipes and organized a match nearby.”

Transforming public space into a football pitch was one of Him’s many ideas, Him further co-created a metal sculpture with the community and a metal work store, which was placed on the roof of one of the building facing demolition. It is a public art to pay homage to the history of pigeon racing which also serves as a kind of ‘guardian’ to the neighbourhood. “As the government always sent their demolition team to tear down buildings at night, the metal sculpture would make their life more difficult while alerting the citizens that the demolition team is on the move.”

All these happened during a period of a few years where urban redevelopment was hitting nearly every district in Hong Kong, making heritage conservation the new buzzword for everyone who cares for the future of our city. When Him was working for the Hong Kong Story House in Wan Chai, Blue House was also one of the main initiatives of urban regeneration as the renewal scheme for Lee Tung Street had commenced. Him gathered a group of concerned citizens to study the history and the culture of the different communities, hoping to build up social awareness and public participation towards heritage conservation. They organized workshops with craftsmen and organic farmers to share with the public the traditional spirit of craftsmanship and living culture. Him recalled that these renewal initiatives had garners some concern over the potential of catalysing another way of gentrification, as developers’ flood in with investment to turn the whole neighbourhood upside down. However, Him did not see such drastic change during his 4 years living in Wan Chai, ‘Besides the opening of a couple of new pubs and the closure of a few car repairs garages, I didn’t witness a big change. Besides, I don’t think the garages were forced out of the neighbourhood by gentrification; the industry was already facing decline to a certain extent.’

Whenever engaging in the discussion of gentrification with the public, Him always starts clarifying and defining what ‘gentrification’ means in the audience’s eyes. Is it just a fancy word for the emergence of cafes and pubs? If we take the definition from British sociologist Ruth Glass who first coined the phase in 1964, gentrification is the phenomenon of urban renewal where the existing low-income, aging or ethnically-minor residents were gradually ‘replaced’ by a group from the ‘gentry’ class - people with higher social status. Therefore, it is not enough to tell whether a district is impacted by gentrification just by the existence of café and artsy stores. ‘We need to think about the motives behind the new businesses, and how they run it. As far as I know, most of these small-scale shops have no intention in bringing along with them rent surge or raising land value.’

As cultural industry is somehow being labelled as the main driving force of gentrification, Him, as an artist, thinks that the term ‘Art and Culture’ can be highly commercialized nowadays as a symbol or a marketing tool to raise the value of a product. “We need to know the fact that most of the time, way before the cultural industry is being criticized for being the culprit of gentrification, the Government and the developers already planned the redevelopment project.’ The artists have been protesting the redevelopment of Sham Shui Po before the public joins the discussion of its gentrification, Him added.

Him further uses ‘The Mills’ in Tsuen Wan, a redevelopment project that involved art and culture elements, as an example to illustrate how we should make our judgment on whether gentrification is taking place. “We need to first look into whether the industrial buildings surrounding The Mills are applying for changes in land use before and after the redevelopment. For me, I do not see such change around the area.’

If gentrification is being described as one of the city development models, then, Him believed, it might be inevitable. “Like the Lee Tung Street project, if in fact the previous occupants have wanted to move out while the developers were interested to develop that area, then redevelopment might not be as bad as it seems. It is only a negative process if it is one that is completely top-down and the people did not have a say.”

In Him’s opinion, what can everyday citizens with little-to-none leverage do in the face of these constant urban redevelopments? “If you do not like it, tell some, file a complaint, make your voice heard! If you find that new pubs annoy you, look for opportunity within the community to speak up. You do not have to organize anything, just put up your own poster to talk about it. Do not always expect the district councillor to bring changes, as their voice can be just as insignificant at times, there are things that we can just do ourselves.”

Photos source: zoom.in.hongkong , Him Lo

Location: Hong Kong

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: