首爾吉事:舊區活化,清拆重建以外,另有選擇?|GUTS in Seoul: Breaking new ground: rejuvenating old neighbourhood without demolition

要解決巿區老化的問題,我們習慣談成本效益、用快捷直接的辦法:清拆重建。不過,重建之後,舊區雖然煥然一新,但總是帶來士紳化的問題,原居民被遷走、新樓租金昂貴,連帶整個區域的生活模式都有連根拔起的改變。吉人若拉闊想像,會否找到一個方法,讓原居民留下,同時可以重振舊區活力?

面對同類的問題,外國政府沒有因為問題棘手而撒手不管,放任發展,近年相繼嘗試在城巿更新的項目中增加規管,避免新發展忽略了基層巿民的需要,例如澳洲墨爾本巿政府在今年3月發出諮詢文件,建議規定未來所有舊區重建的住宅項目中,必須提供至少25%的樓宇為可負擔房屋。

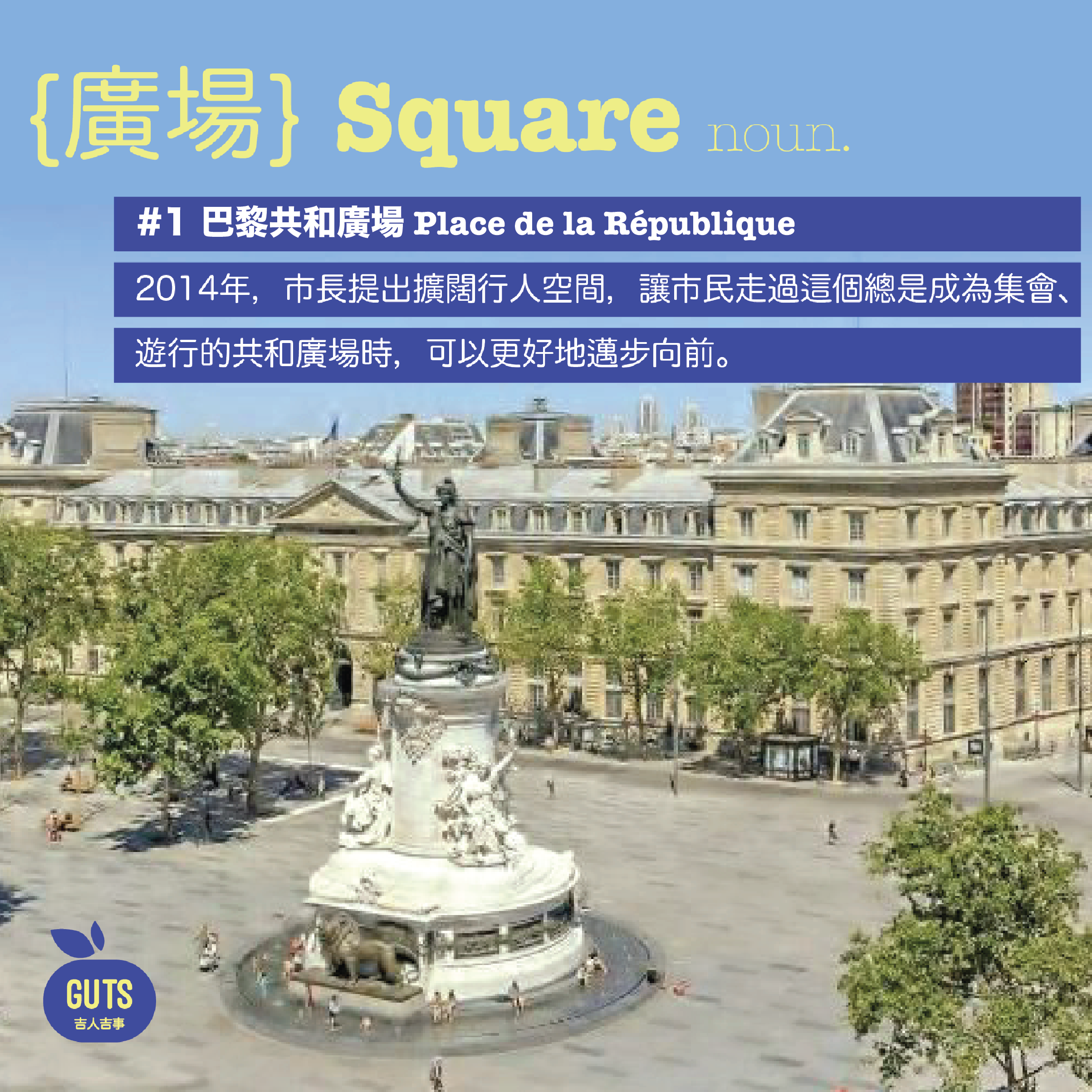

毗鄰香港的亞洲城巿 - 首爾,當地為減少重建帶來的破壞,更嘗試徹底改變一貫以來清拆重建的模式:2012年,新任巿長朴元淳公佈《首爾巿政府修改新城與重建計劃的方案》,把城巿發展方向由「開發」轉為「維護與保存」,把舊城重新發展的項目稱為「城巿再生」,強調居民主導發展、強化原有社區網絡。政策推出後,首爾巿政府開始著手針對人口減少、建築物老化,以及在產業衰落的舊區,製訂「再生」計劃。不拆樓,如何改善舊區?我們可先看看解放村的個案:

解放村位於首爾核心地帶,日治時期曾為日軍的射擊場,並建造了「京城護國神社」。戰後,美軍接管解放村但沒實質管理,引來大批戰爭遺民、北韓人及農民移居此地。由於有大量勞動人口,解放村在1970年代的針織業相當蓬勃。直至90年代,產業走向式微,人口轉趨老化和銳減。2014年,巿政府研究重新發展解放村,摒棄過往發展商的合作模式,直接與居民開會商討發展方向,投放約7,000萬港元,包括修葺建築和改善設施。不過,翻新工程並沒有為解放村改頭換面,街道景觀依舊,小店林立,原居民和商店幾乎是原封不動,而原本吉舖則陸續有書店、咖啡店、藝術家工作室等遷入。

除了以保留村落面貌為原則,政府亦盡力確保原居民留在解放村,例如與業主簽署協議,確保2016年至2022年的租金不變;為減少新舊居民的磨擦,政府亦鼓勵他們為停車、棄置垃圾等方面共同制定規則。目前解放村的人口,與2015年相比已回升三成。

解放村並不是首爾「城巿再生」的唯一例子,位於首爾西北邊的香林社區,居民亦選擇了以拆舊樓、起高樓之外的方式改善社區環境。除了翻新舊樓、清理巷弄等,香林社區的居民,更以政府提供的經費,買下閒置房屋,以低於巿價的租金租予年輕人。

如此說來,香港其實也不是未試過用這種「再生」方法,例如灣仔藍屋的「留屋留人」活化方案,可說是破天荒的嘗試。不過,相對於活化一個社區,藍屋的規模相對較小,而且藍屋之後,這種模式仍未在其他項目出現過。「巿區更新」是否只可以由舊樓換成一棟又一棟高樓大廈?首爾的吉事正展示了,居民如何透過共同規劃再生計劃,繼續留在自己所營造的社區生活。

地點:墨爾本、首爾、香港

Breaking new ground: rejuvenating old neighbourhood without demolition

The conventional approach in redeveloping an old neighbourhood, is ‘uprooting’ the existing infrastructure to rebuild another one. Cost-effective and straight forward it may seem, such act simultaneously introduces gentrification where the existing low-income residents is ‘replaced’ by people with higher social status. Are there other ways to rejuvenate the neighbourhood without expelling the existing residents?

Around the globe, governments from big cities have tried to enact new regulations to tackle such issue. In March 2020, Melbourne city council in Australia released a new consultation paper and suggested that all redevelopment projects should reserve 25% residential area for affordable housing. In Seoul, the government further push forward a transformative change in policy, aiming not to follow the status quo of demolishing and rebuilding the district. The former mayor Park Won-soon released a new redevelopment policy in 2012, redefined the goal of urban renewal from ‘development’ to ‘preservation and conservation’. He even renamed ‘redevelopment’ to ‘rejuvenation’ in official paper, with focus on strengthening community network and being citizen-led. Haebangchon, one of the oldest neighbourhoods in central Seoul, is a demonstration on how to rejuvenate a district without large scale demolition and redevelopment.

Situated in the heart of Seoul, Haebangchon, which literally means ‘liberated village’, was originally a military shooting field of the Japanese army. After liberation, the US army took over the area but maintained a loose control, indirectly leading the area to become the homes of refugees, peasants, and people who fled from North Korea. From 1970 onwards, the knitting industry was flourishing in the area until the industry decline in the 90s. In 2014, the government of Seoul initiated a rejuvenation project of Haebangchon. Unlike conventional projects that worked with developers, the authority adopted a whole new collaborative approach with the residents and invested $70 million HKD to upgrade the facilities and preserve the buildings. The renovation works did not aim to turn the place upside down. The streetscape of the redeveloped Haebangchon remained the same, small businesses, shops and residents remained. Furthermore, new bookshops, café and artist studios gradually moved in.

Apart from preserving the outlook of Haebangchon, the authority is thoughtful in keeping the community in good shape. The cost of rent remained stable as the property owners are bounded by an agreement to keep the same rate from 2016-2022. Moreover, the government encouraged the residents and the newcomers to co-create social rules together, such as agreeing on the etiquette of car parking and disposal of garbage, to facilitate a better integration of new and old residents. Currently, the population of Haebangchon has grown for 30%.

Haebangchon is not the only successful case of city rejuvenation in Seoul. In Hyangrim, north western part of Seoul, the residents also opted for an alternative way in bringing new energy to the neighbourhood. Besides renovating old buildings and organizing the streets, the residents invested in buying vacant flats with government subsidy. These flats would be rented to young tenants at a price below market rate.

The alternative approach in urban renewal project is no alien to Hong Kong. In fact, Wan Chai Blue House is revitalized with the aim of preserving the property, its residents and community. This revolutionary approach, sadly, is yet to flourish or to be further extended to larger scale redevelopment projects in Hong Kong. The cases in Seoul are solid demonstrations on how successful redevelopment projects can be when cocreating with residents. Urban rejuvenation is never a single path of uprooting the existing community and ‘renewing’ into another world, there are better ways waiting for visionary GUTSMAN to take a ground-breaking step.

Photo source: Internet, The Korea Herald, The Seoul Metropolitan Government

Location: Melbourne, Seoul, Hong Kong

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: