健康城市:「健康」一詞的演進如何影響城市規劃、空間設計和使用?|Healthy cities: How has the evolution of the concept of "health" impacted urban planning, spatial design, and usage?

説起「健康城市」,你會想起什麽?是醫院、診所, 還是公園?這些空間以外,你又有否留意到,「健康」其實與整體城市規劃和空間設計息息相關?當我們對「健康」的理解改變時,城市空間往往亦會因而改變:由初時的基礎衛生建設、建築物規範,到醫療、社福照護設施的發展,以至是康體設施和公共空間的規劃,都反映著社會當時對「健康」的理解。本月的吉人吉事將會透過回顧「健康」一詞的演進,檢視不同城市空間的演變探討規劃和設計可如何回應轉變中的健康需要,更全面地推廣全人健康。

瘟疫來襲:以衛生、治療爲重的規劃和設計

回顧歷史,在城市化的進程中,瘟疫往往是改革建築物設計、推動城市衛生建設及規劃的主因。由19世紀肆虐歐洲的霍亂,到後來的鼠疫,都促使了各地政府認真審視環境衛生,發展基礎衛生建設,以及規範住屋環境。

香港亦不例外,開埠初期極為盛行的瘧疾(又稱「香港熱 Hong Kong Fever」)促使了港英政府正視當時惡劣的衛生情況,著手發展食水、污水處理等基本衛生建設,成功令傷寒死亡率大幅下降。後來的鼠疫更推動了建築物條例及公共醫療設施的發展:

《1903年公共衞生及建築物條例》(1903 Public Health and Building Ordinance),試圖透過規範華人居所的設計:例如成人人均居住面積不得少於50平方英尺、建築物必須有後巷、睡房必須有窗等,以解決人口密度過高、通風採光欠佳、人畜共住等而起的種種問題。

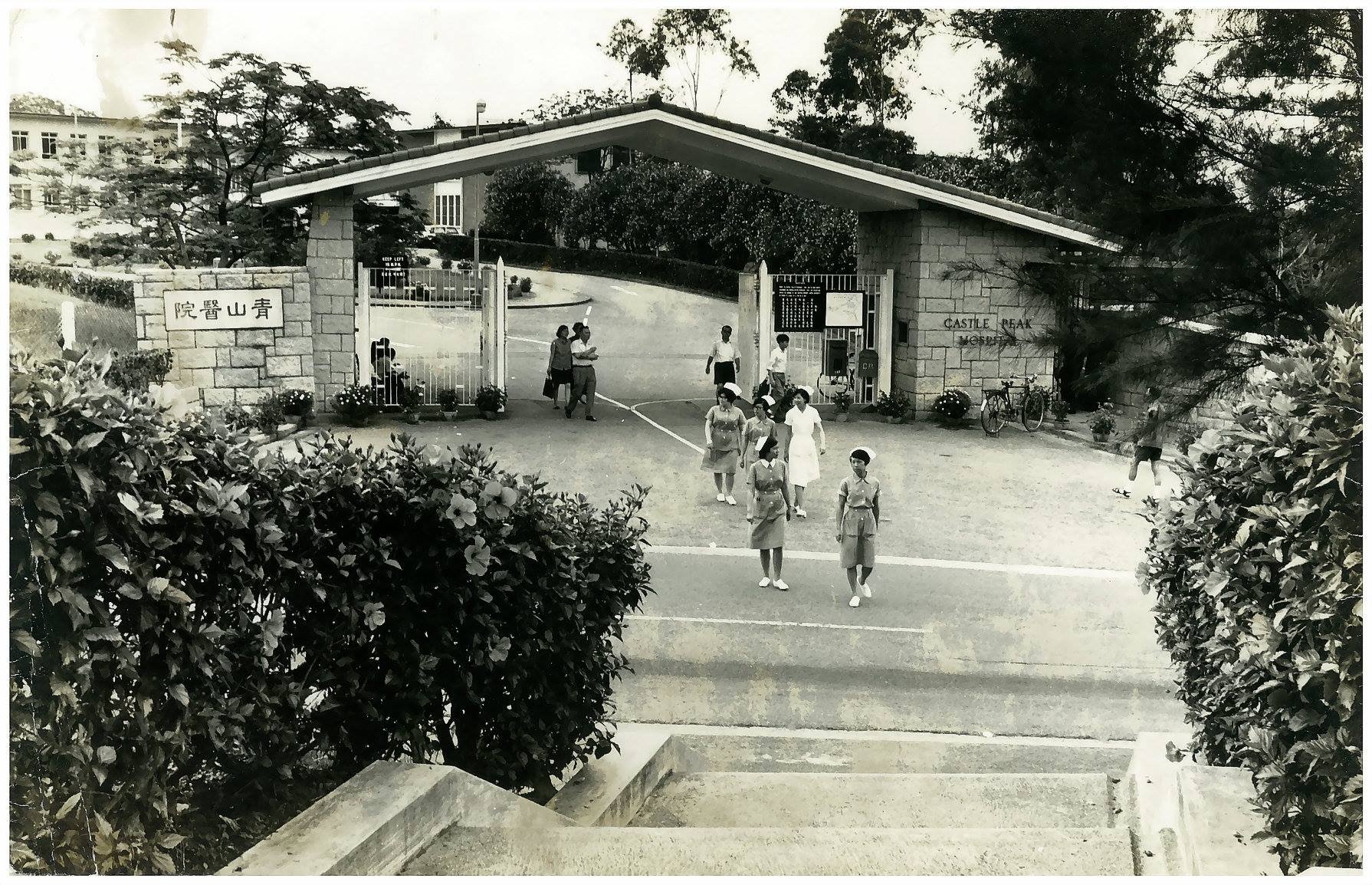

在西營盤一帶的華人聚居地興建公共醫療設施,例如現為二級歷史建築的第二街公共浴室,和位於西邊街的舊西約公立方便醫局。

而香港首個公共公園——卜公花園,亦是因太平山一帶華人人口密度過高為由收地建成的,可見衛生觀念對城市基建發展和建築物設計的影響之深。

與時並進:從衛生、治療到復康、安老和社福

隨著傳染病逐漸受控,衛生建設和公營醫療系統漸趨成熟,經濟穩步發展,不少城市都迎來新的健康需要。此時,「健康」一詞的焦點已由應對瘟疫和衛生問題,慢慢擴展至復康、精神健康、安老和預防慢性疾病等議題。醫院、診所、療養院等以治療為重的設施固然重要,但面對這些嶄新的健康需要,更加需要社會福利政策、服務模式,以及空間規劃的配合。

自上世紀50年代起,香港亦開始因應這些需要建立更全面的醫療、社福設施和服務,當中有不少均由慈善組織牽頭發展,及後才成爲公營醫療又或社會福利系統的一部分,例如現時的:

在規劃和空間上,不同類型的設施亦因政策方向、人口結構和服務模式轉變順應而生。其中一例便是本港社區安老設施的發展,其起源可追溯至70年代初老年人口大幅上升,但缺乏照料長者的公共資源。當時只有由少數團體營運、專門收留身體健全長者的的「老人宿舍」。不過,一旦長者身體機能衰退、失去自理能力便需離開。於是,社會關於長者健康、福利和保障的討論開始升溫,促使政府關注長者議題,亦陸續批出土地讓不同社福機構開辦「護理安老院」、「老人中心」等設施。

現時「居家安老為本,院舍照顧為後援」政策方針下,社區安老設施大致可分爲院舍照顧與社區照顧兩大類。前者專為照顧殘弱及長期病患長者,而後者則可再細分爲「家居爲本」和「中心爲本」服務,主要在以下設施進行:

日間護理中心:為身體機能有中度或嚴重缺損的長者提供日間照顧服務

長者地區及鄰舍中心:為居於社區的長者提供輔導、外展、轉介及社交康樂活動等服務

《香港規劃標準與準則》(Hong Kong Planning Standards and Guidelines) 而定。以上例子都足以說明,「健康」一詞的演變對社會福利政策和空間規劃的影響之大。

全人健康:從環境因素入手

由初時只為解決當務之急而發展的基礎衛生和醫療建設,到結合社會福利政策的各項復康、照顧和支援設施,確是一大里程。然而。由於社會資源有限,設施規劃和服務名額遠不上人口增長,即使「健康」的定義早已涵蓋心理及社交健康,實際上亦只能優先回應最逼切的醫療和照護需要,在此之上的需求則留待家庭、市場、非政府組織自行應對。

踏入千禧年代,世界衛生組織 (WHO) 提出更全面的「國際功能、殘疾和健康分類系統」 (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health),强調「健康」的組成不只由身體功能和構造組成,還有活動與參與 (activity and participation),而影響健康的因素亦不限於個人 (personal factor),亦有環境因素 (environmental factor)。在此框架下,「回復健康」不止是醫學上的痊癒,亦不應單靠傳統醫藥為主的治療,而是需要最大程度上回復、甚至提升個人日常生活和社交參與的能力。

這些「健康」定義上的改變均令不少學者、設計師和建築師們開始思考,除了推動宏觀政策和規劃上的改革,能否先從現有的設施入手,透過改造空間佈局和室内設計等,為用家帶來更便利、舒適和人性化的體驗,從而促進健康?事實上,近年常應用於社會房屋、兒童之家等的 「創傷知情設計」(Trauma-informed design) 概念,便是以環境因素為出發點。結合心理學上對創傷的研究,先辨認容易觸發心理創傷的空間元素,例如聲音、氣味、觸感等,然後再透過空間改造,營造出舒適且具安全感,能夠促進創傷復原及個人發展的空間。

大至城市規劃,小至個別空間設計,其實都與社會當時對「健康」的理解息息相關。在下一篇,吉人吉事將分析不同案例,看看設計團隊運用哪些策略,營造出「健康」空間。

When you think of "healthy cities," what comes to mind? Hospitals, clinics, or parks? Beyond these spaces, have you noticed that "health" is closely related to overall urban planning and spatial design? As our understanding of "health" alters, urban spaces also often undergo transformations. From the initial focus on basic sanitation infrastructure and building regulations to the development of medical and social welfare facilities, as well as the planning of recreational facilities and public spaces, they all mirror society's understanding of "health" at that time. This month’s GUTS will review the evolution of the concept of “health” by examining the changes in different urban spaces. It will also explore how planning and design can respond to evolving health needs, and promote holistic health more comprehensively.

The epidemics’ strike: Prioritising hygiene and treatment in Planning and Design

Throughout history, epidemics have been catalysts for building design reforms, urban health infrastructure and planning development. Cholera outbreaks in 19th century Europe and later cases of the bubonic plague prompted governments worldwide to address environmental hygiene, develop basic health infrastructure, and regulate housing conditions.

Hong Kong, too, experienced the impact of epidemics during its early colonial period. The prevalent malaria outbreak, known as "Hong Kong Fever," urged the British colonial government to address unsanitary conditions. They began developing basic sanitation infrastructure, such as clean water supply and sewage treatment, which successfully reduced the mortality rate of typhoid. The bubonic plague further spurred the development of building regulations and public medical facilities:

The 1903 Public Health and Building Ordinance attempted and aimed to regulate the design of ethnically Chinese dwellings. For example, it stipulated that the average living space per adult should not be less than 50 square feet, buildings must have rear lanes, and bedrooms must be equipped with ventilated windows. These regulations aimed at addressing issues arising from high population density, poor ventilation, and cohabitation of humans and animals.

Public medical facilities were constructed in Chinese residential areas in Sai Ying Pun, such as the Second Street Public Bathhouse, which is now a Grade II historic building, and the former West Point Chinese Public Dispensary located on Western Street.

Another significant development influenced by hygiene concepts was the establishment of Blake Garden, Hong Kong's first public park. It was created by reclaiming land in the Tai Ping Shan area to alleviate the high population density among the Chinese community. These examples demonstrate the profound impact of public hygiene on urban infrastructure development and building design.

Keeping pace with the changing health needs: From hygiene, treatment to rehabilitation, ageing, and social welfare

As infectious diseases gradually came under control, health infrastructure and public healthcare systems matured, and the economy steadily developed, many cities faced new health needs. The focus of "health" gradually shifted from addressing epidemics and hygiene issues to encompass rehabilitation, mental health, ageing, and the prevention of chronic diseases. While treatment-focused facilities such as hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes remain crucial, addressing these emerging health needs also requires greater coordination between social welfare policies, social service models, and spatial planning.

Since the 1950s, Hong Kong has also inaugurated measures to establish more comprehensive medical, and social welfare facilities, and services to meet these needs. Many of these initiatives were initially spearheaded by charitable organisations, which later became part of the public healthcare or social welfare system. Examples include:

In terms of planning and space, different types of facilities have emerged in response to changes in policy directions, population structures, and service models. One example is the development of community-based ageing facilities in Hong Kong. This can be traced back to the early 1970s when the elderly population increased significantly, but public resources for elderly care were lacking. At that time, there were only a few "elderly hostels". Operated by a small number of organisations, they only cater to physically fit seniors. Once the seniors experienced declining physical function and loss of self-care abilities, they had to leave these facilities. As a result, discussions on the health, welfare, and protection of the elderly gained momentum in society, leading the government to pay attention to elderly issues and gradually allocate land for various social welfare organisations to establish “care and attention homes” and "elderly centres."

Under the current policy of "ageing in place as the core, institutional care as back-up," community ageing facilities can be broadly categorised into two main streams, namely the institution-based care and community-based care. The former is designed to cater to frail and chronically ill seniors, while the latter can be further divided into residential care services (RCS) and the community care services (CCS), mainly provided through the following facilities:

Day Care Centres: Provide daytime care services for seniors with moderate or severe disabilities.

Neighbourhood Elderly Centre & Elderly Centre: Offer counselling, outreach, referral, and recreational activities for community-dwelling seniors.

The location selection, floor area, service capacity, and other factors of these service facilities are stipulated by the Hong Kong Planning Standards and Guidelines. The examples above illustrate the significance of the evolving concept of “health” on social welfare policies and spatial planning.

Holistic health: Environmental factors as a starting point

The journey from developing basic hygiene and healthcare infrastructure to integrating rehabilitation, care, and support facilities with social welfare policies has been significant. Yet, due to limited social and spatial resources, service availability has not kept up with population growth. Even though the definition of "health" already evolved to encompass mental and social well-being, the public welfare system is slow to catch up, leaving non-urgent healthcare needs to the hands of families, the private market, and non-governmental organisations.

Entering the new millennium, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the more comprehensive "International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health". It emphasises that "health" is not solely determined by bodily functions and structures, but also by activities and participation. It also recognised that factors influencing health extend beyond personal factors to include environmental factors. Within this framework, "health and recovery" goes beyond curing and should not rely solely on traditional medical treatments but should aim to restore and enhance individuals' abilities in their daily lives and social participation.

These changes in the definition of "health" have prompted scholars, designers, and architects to consider whether they can start by transforming existing facilities as macro-level policy and planning reforms progresses. This can be achieved through better layout and interior designs that provide users with more convenient, comfortable, and human-centred experiences, while promoting health.

In fact, the concept of "trauma-informed design," which has been frequently applied in facilities such as social housing and Small Group Homes (for children from 4 to under 18 years of age) in recent years starts by taking environmental factors into account. By combining psychological research on trauma, it identifies spatial elements that may trigger psychological trauma, such as sound, smell, and textures. The space is then transformed to create a homy environment that facilitates trauma recovery and personal development.

From urban planning to interior design, they are closely related to society's prevailing definitions of health. In the next article, we will analyse different case studies to explore design strategies to create "health-promoting" spaces.

延伸閲讀/資料來源

Further Reading / Source:

Chan-Yeung, M. M. W. (2018). A Medical History of Hong Kong: 1842-1941. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: