公共建築系列:監獄設計|Public architecture series: prison design

在談論香港的公共建築時,總會提及到圖書館、體育館、球場等。不過,所謂公共建築不止包括文康設施,還有公共衛生設施如公廁,以及被規劃在日常生活視線範圍以外的設施,例如殮房,例如監獄。位置偏遠,並不代表它們不重要,這一個月的吉人吉事,將嘗試與吉人討論很少人談及的監獄設計。

在進入討論、觀看其他國家的設計案例之前,不如先從了解香港監獄歷史開始——

根據懲教處網頁的數字,截至2019年3月,若撇除戒毒所、教導所、更生中心等,全香港共有13座監獄,囚禁總人數約7,600人。雖然監獄在現今社會並不是新鮮事,不過原來在開埠之初,監獄一座就夠,事關當時懲處犯人的方法,主要不是監禁,而是當眾鞭打、遊街等。

1859年的英文報章《孖喇西報》(Hong Kong Daily Press),曾經記錄了當年的鞭刑,形容群眾聚集在空地觀看犯人被鞭打至皮開肉綻,除了具有觀賞性、有助公眾確立優劣之別,報章同時還建議把執行的地點移師至法院外,方便達官貴人履行他們作為觀看者的責任。1866年上任的第六任港督麥當奴,曾鼓勵警察公開鞭打華人作為管治社會的方法,那時候,警察幾乎每天在皇后大道當眾鞭打華人,至1871年,政府甚至規定逢星期三為「鞭笞日」。

在十九世紀的香港,一般華人貧窮、無法繳交罰款,鞭打是主要的刑罰方法,其他還有剪去長辮、遊街示眾等,以羞辱作為懲治。直至1876年後刑罰制度有所改革,監禁才逐漸取代公開施刑及流放等。這種改革的理念,源自於英國的基督教相信監禁是讓犯人悔改、防止他們重犯的更好方法,也對社會更有益處,例如犯人要在監獄中做苦工、揼石仔。

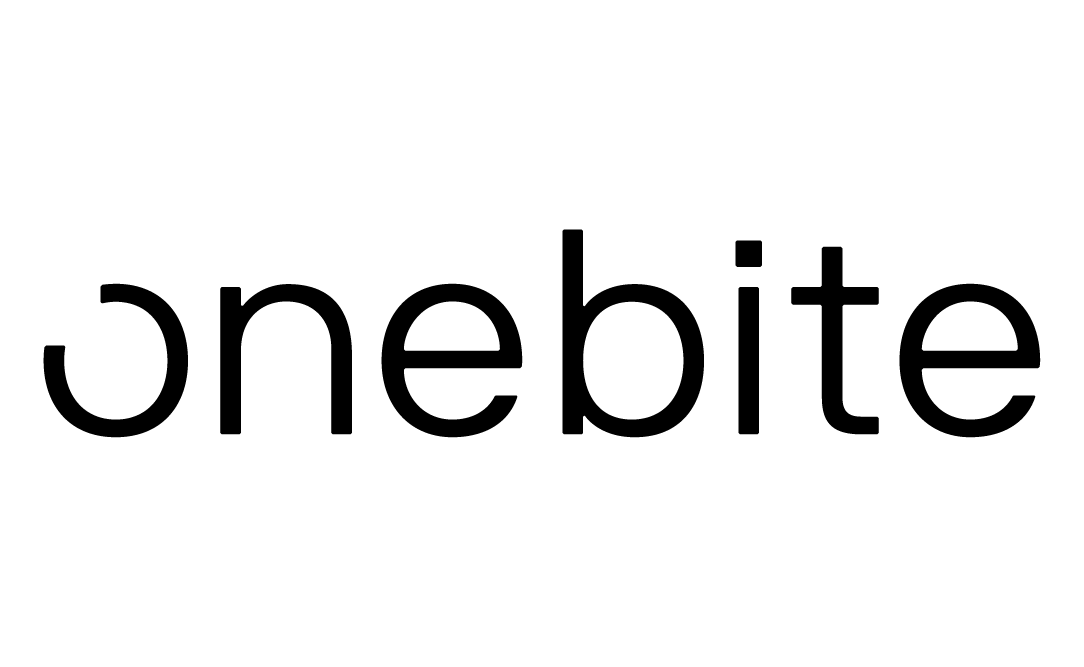

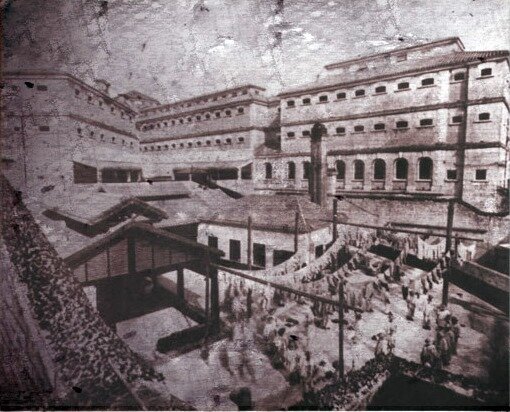

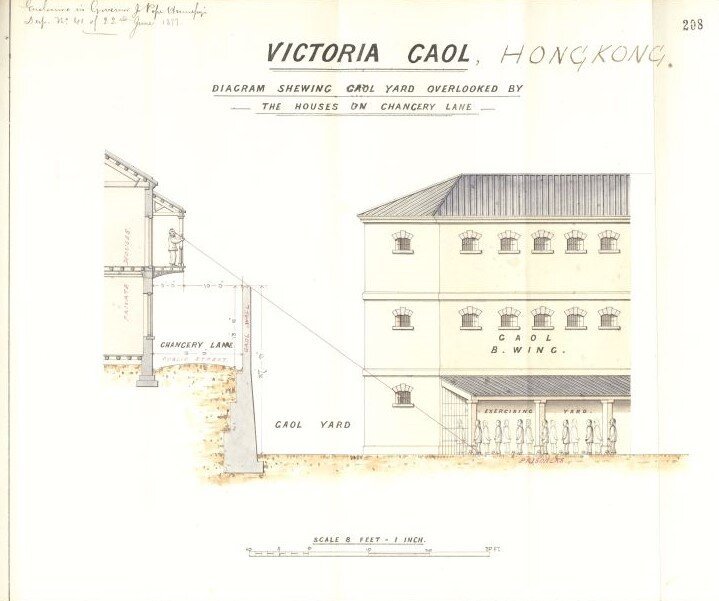

由於囚禁的人愈來愈多,香港參考了美國費城1829年建成的東方州立監獄,把域多利監獄(中央監獄)於1858年,重建成「放射式」的監獄佈局,整個建築群以一座中央塔為核心點,由5座監倉建築物包圍。這樣的佈局,讓中央塔裏的官員可以同時監視所有監倉,以有限的獄吏可管理最多的囚犯,提高效率。在域多利監獄之前,英國倫敦早把這設計套用在本頓爾監獄及旺茲沃思監獄。

但重新設計的域多利監獄,仍是無法滿足日益增多的囚犯,1890年至1930年的40年間,囚犯人數由486人倍增至1175人。1937年,被譽為殖民帝國首屈一指的赤柱監獄落成,由6個監倉組成,可容納達1,500人,在當時是高度設防及先進的監獄。不過,及後大量內地人為逃避內戰及日軍非法到港,令赤柱監獄也迅速出現人滿之患。

相片來源:網上圖片

Through vivid first-hand accounts, a 1859 newspaper report in Hong Kong Daily Press provided a glimpse of what had been a monthly spectacle and a source of macabre entertainment for colonisers, taipans, and common masses alike in the 19th century.

“To witness a string of wretches writing and howling under the awful torture of the lash, and to count the thuds that are resounding off bare flesh of a fellow being, is not one would think, a very aesthetic enjoyment, but the crowd taking up the space in front of the post of dishonour would seem to indicate the contrary. Indeed, if we were not of opinion that the laudable object of public flogging is intended by its very repulsiveness to strike terror into the hearts of other malefactors, we should advocate a removal of the post to somewhere opposite the Supreme Court, to make it more convenient for the gentry who go so much of their way at present to ‘assist’ at this salutary and necessary public duty.”

Flogging was the most common form of punishment for locals running afoul of the law. Those too poor to pay fines, were instead generously beaten. Other unorthodox punishments in the colony’s early establishment included cutting off the offenders’ plaited queues and parading them across the Chinese settlement shackled in bulky stocks with the offenders’ name and nature of his crime prominently stated. Public punishment was then preferred to lengthy imprisonment as popular consensus deemed shame to be an effective crime deterrent, both for crowds witnessing the spectacle and those suffering from the pain inflicted.

Imprisonment only became the default punishment after 1876, following the revised Regulations for the Gaol which gradually phased out public punishment and forced deportation for severe crimes. Instead, prison sentences and corresponding forms of hard labour were meted out. These changes in Hong Kong were motivated by Christian religiosity in Victorian Britain which favoured incarceration as effective methods for prisoners to repent for their offences and deter them from committing them again. The type of work ranged from oakum picking (pulling rope thread apart to use as caulk to seal joints on ships), breaking stone, and using the crushed aggregate to build new roads.

With more prisoners incarcerated but only a small group of European wardens and Indian guards available to operate the gaol and maintain its security, Victoria Gaol was redesigned in 1858 with a radial plan to provide greater surveillance and to isolate the prisoners visually from each other, such that the prison could be run more efficiently with less guards. The design originated from the Eastern State Penitentiary (built in 1829) in Philadelphia, USA and was subsequently adapted by British architect, William Crawford, for Pentonville (1842) and Wandsworth (1851) Prisons in London. Hong Kong’s Victoria Goal in the late 1800s likewise spotted a spoke-like structure with a central tower radiating out to five cell blocks that allowed guards in the central hall to maintain visual contact with those patrolling the cell blocks and raise alarm if any disturbances occurred in open yards in between the blocks.

As the daily average number of prisoners in Victoria Gaol progressively increased from 486 in 1890 to 1,175 in 1930, it was clear that a modern prison complex was needed to cope with new challenges in policing and rehabilitation. When opened in 1937, Stanley Prison was described as the “finest prison in the colonial empire”. Comprising six cell blocks set in a one square mile site behind 18-feet thick compound walls, the prison complex was designed to support 1,500 prisoners with hygienic and secure accommodations. However, that ideal was cast aside quickly as overcrowding became severe with increasing numbers of Chinese immigrants entering Hong Kong illegally to escape civil war and the Japanese invasion.

The next major shift in prison governance happened only in 1981, about a hundred years after flogging, parading offenders in stocks, cutting off their queues, and other forms of spectacle punishment were abolished. Public sentiments towards punishment had shifted from inflicting pain and shame on offenders, to isolating them from the wider society, and finally towards recognising the prison as an institution for rehabilitation, rather than punishment. This is reflected in the renaming of the Prisons Department as the Correctional Services Department and the adoption of the motto “We Care” to embody a more humane approach to integrate prisoners back into society. Prisons were categorised by different security levels, while detention centres, schools and training centres, drug addiction treatment centres, and halfway houses provided differentiated treatment for prisoners.

These new building types represent not only the evolving practice of crime and punishment in Hong Kong, but also how architecture plays an essential role in humanising this change process. This month’s GUTS will continue to explore local and overseas examples of contemporary prisons to shed light on prisons as a marginalised, but definitely not a marginal part of our built environment.

Photo source: Internet

你可能對以下吉人吉事有興趣:

You may also be interested in these GUTS Stories: