Community life on demand in ground-floor shop spaces: Tactical placemaking in Hong Kong

Extracted from

“Community life on demand in ground-floor shop spaces: A tactical place-making initiative in Hong Kong” co-written by Sarah Mui, Johnson Cheung (Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong) and Alan Cheung. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020911671

What is Project House?

onebite launched the urban ‘matching’ platform Project House as a pop-up design to steer city regeneration and community revival. Using a tactical place-making approach, Project House pairs vacant shops with local social groups facing spatial needs. The win–win results bring local exposure to pop-up vacant shops while providing marginalised community groups with adequate space for new social practices.

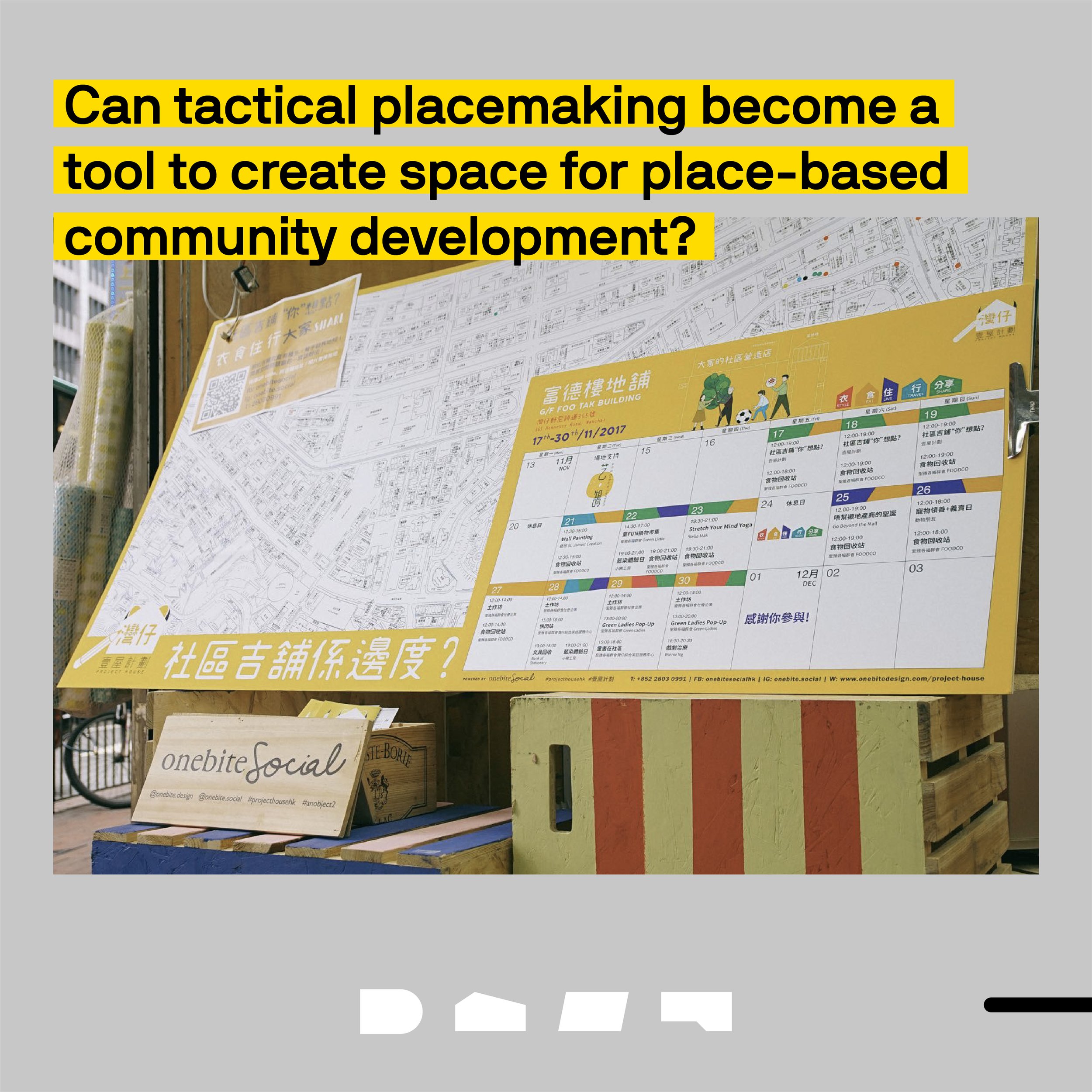

Through this platform, we hope to answer some pertinent questions: Can tactical place-making become a tool to create space for place-based community development? What are the successes and failures of Project House? How can Project House be applied to different contexts?

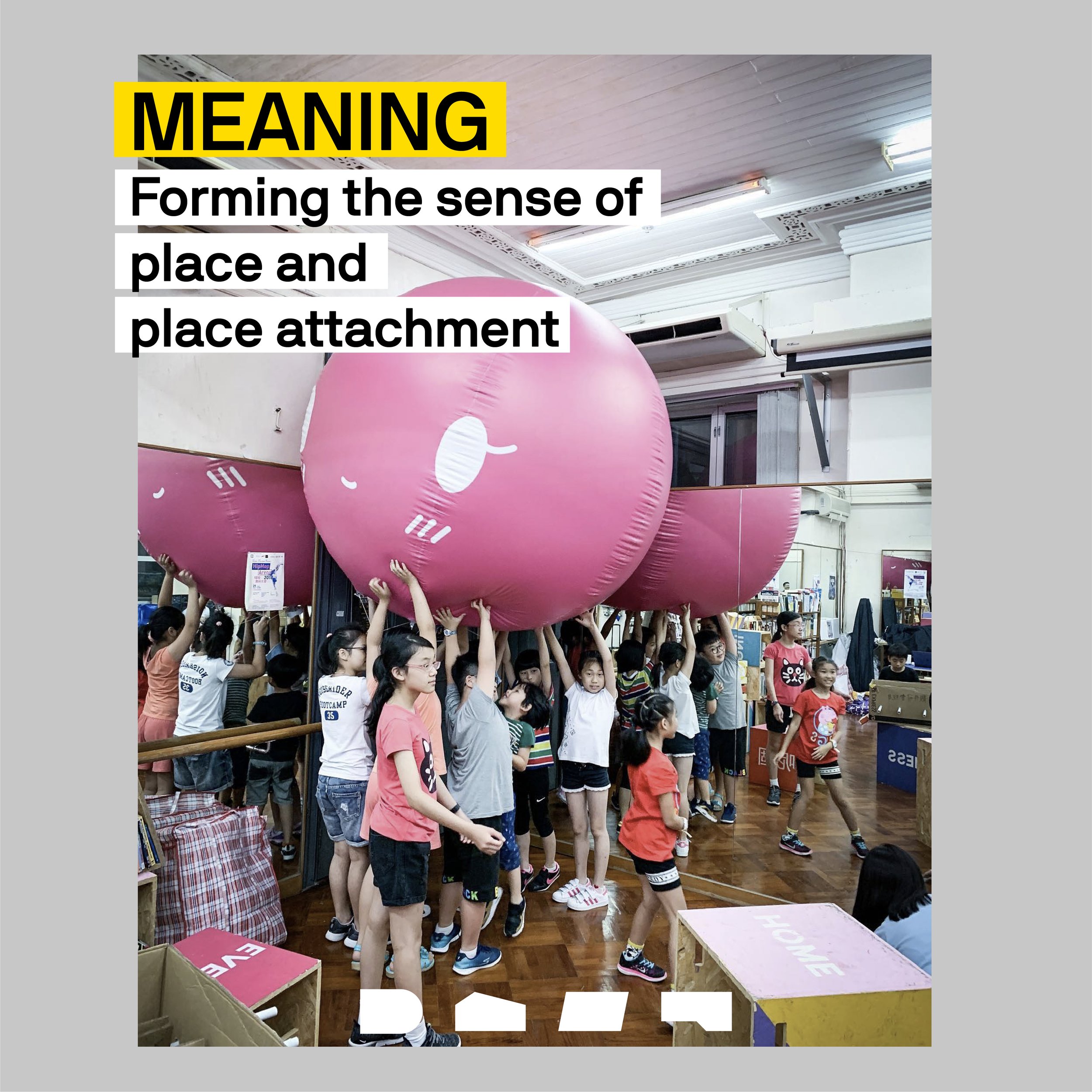

Najafi and Shariff (2011) describe the sense of place from both interpretive and emotional aspects of environmental experience. According to them, the key factors contributing to the formation of the sense of place include physical features of a place that create meanings and conceptions while safeguarding their functions. Place attachment becomes a dimension for measuring the sense of place. Creating cognitive meanings generates emotional connections between people and public space; it strengthens place attachment, and thus achieves the sense of place, which we hope to achieve in Project House.

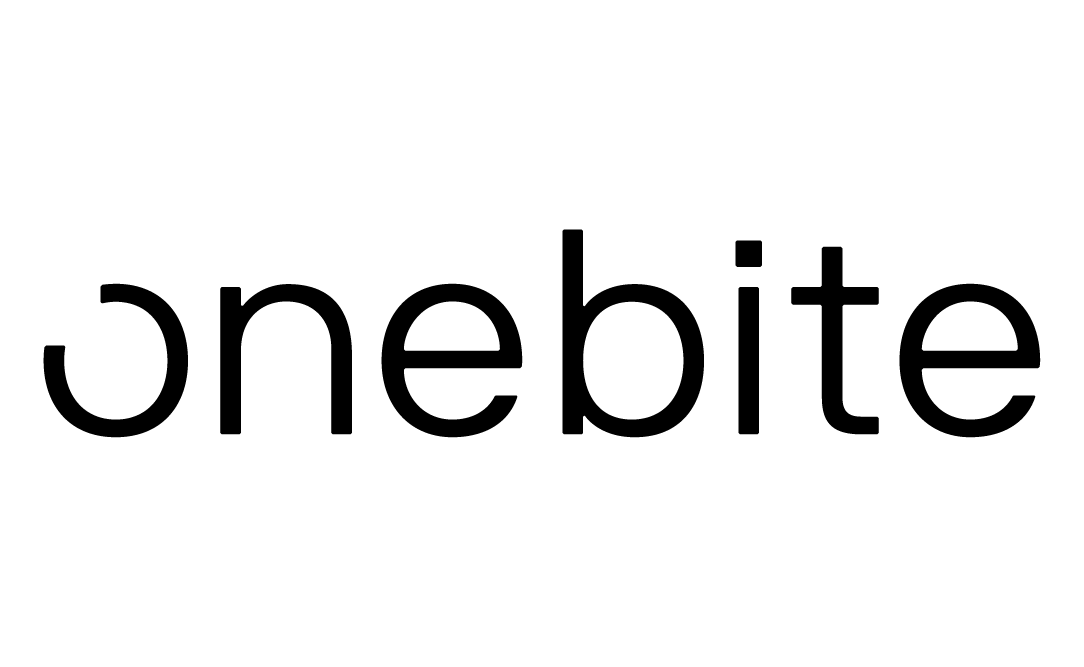

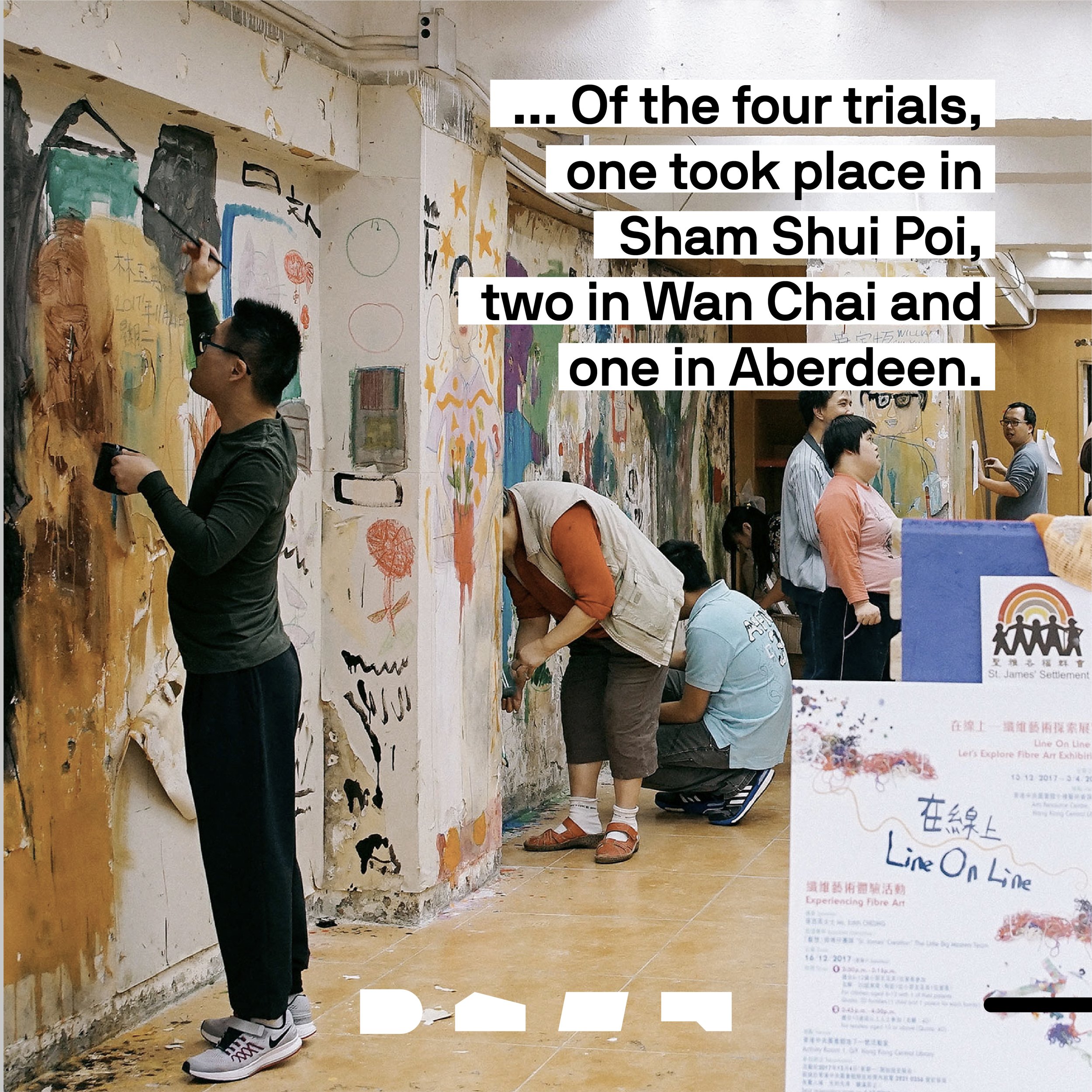

Four Project House trials have rolled out since 2017. The selection of locations was organic. Project House relied on the supply of vacant ground-floor shops. Based on a reverse-thinking model, the contents of Project House were generated based on a confirmed location. Of the four trials, one took place in Sham Shui Po, two in Wan Chai, and one in Aberdeen. These three districts are among the oldest, most impoverished, and most densely populated in Hong Kong. The patterns observed in the trials varied and shed light on the unique character of each district.

Innovative tactical place making creates space for new social practices

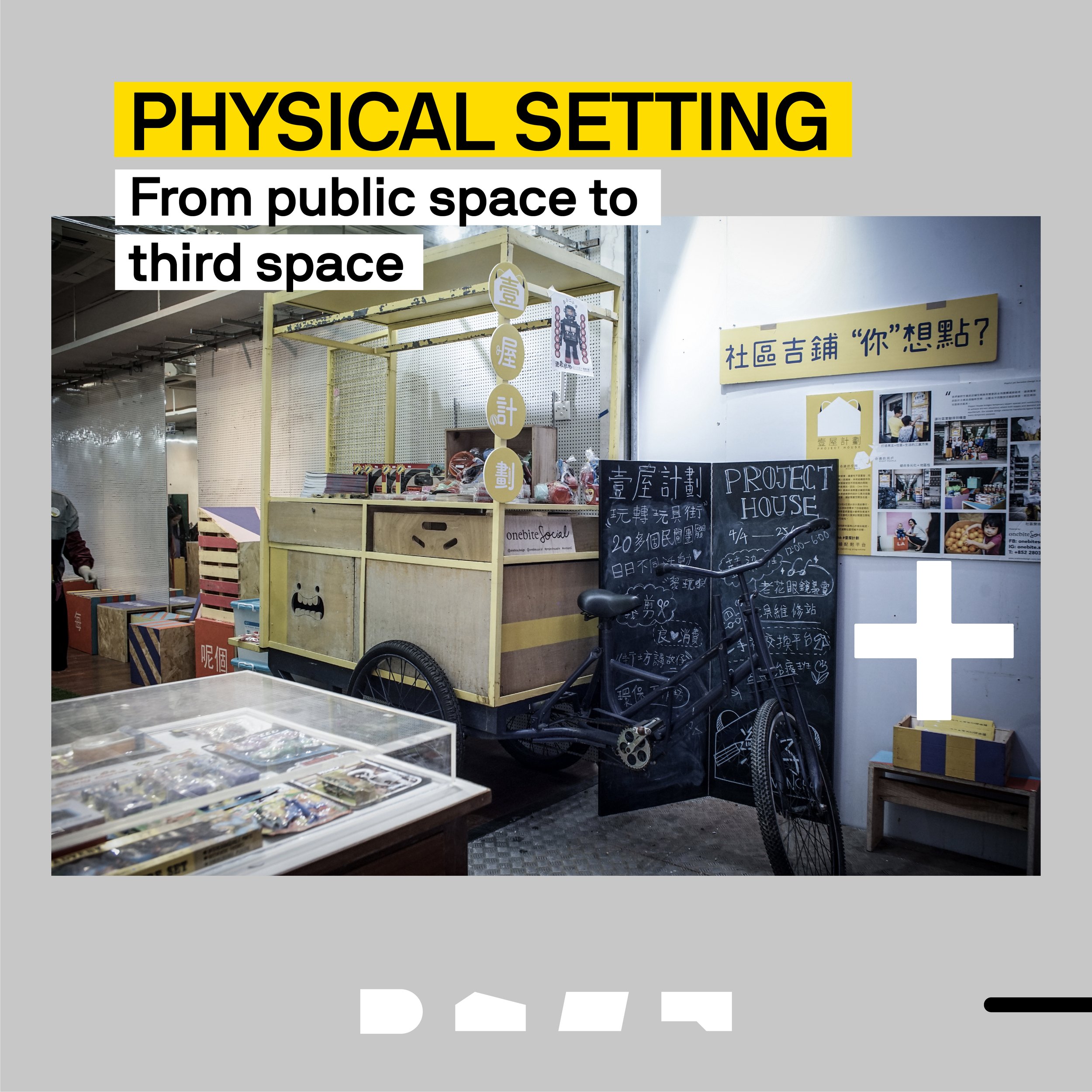

Our social research shows how innovative and tactical placemaking can facilitate new use patterns, particularly when the connection between physical, cultural, and social identities define a place and facilitate an ongoing evolution (Project for Public Spaces, 2000). Based on Lefebvre’s concept, the third space becomes a ‘lived space’. These radical spaces and the marginality between private and public domains allow new insights to emerge in social practice (Lefebvre, 1991; Moles, 2008). To summarise the experience of the four Project House trials, we collected three crucial insights.

First, a neutral platform for collective communities works. Before the birth of Project House, individual organisations implemented their outreach activities only within their existing networks, setting a limit on their exposure potential. Project House offers a shared platform where content is promoted to multiple networks in which all collaborators are active, neutral, and objective. This optimises the promotion impact. Neutrality is crucial, as the objective of Project House is to minimise potential local competition among social work groups, thereby maximising support.

Second, it triggers new forms of social encounters. Project House creates an unconventional space on the streets. Its ‘exoticism’ and striking design animates the streets and appeals to passers-by. Nowadays, people are used to typical streetscapes with chain stores. Project House challenges the status quo by replacing vacant spaces with a friendly local attraction, giving passerbys a reason to pause and to walk in. Place and space combine to create a new front yard for active social life.

Third, innovative user need matching helps to strengthen a new community-based social compact. Without neglecting the commercial values of ground-floor shop space, Project House carefully conducts matching according to the rule of ‘value at front, community at back’. The rule divides each shop space according to commercial value and the ability to attract passers-by through products and purchases. Therefore, the facade area of the shop is used by social enterprises or local start-ups for retail purposes, while the back area is allocated for community events. Such matches target specific users and customers with shared characteristics. For instance, when there is an event for children, the retail section will display children’s or family products. Where a specific time slot is designated to products for the elderly, the community workshop at the back will be curated for this specific clientele. This matching system gathers different user groups more efficiently to target both community events and products. Attracting the right people at the right time for the right activities helps to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of new social practices being tested.

Can tactical place-making become a tool for place-based community development

Street life depends on what a public space can offer besides huge floral displays and fountains. Although front yards have played a crucial role in fostering social life on city streets, however, if we do not have such components in Hong Kong, what can we do to foster community development? One potential solution lies in creating more ‘third space’, for example, identifying and using transitory vacant ground-floor spaces, and curating its use as we have done so in Project House

Nowadays, we live in a fluid and transient world, and public life changes faster than the built environment. The mobility of lifestyles may be a good match for physical congestion, as people are becoming used to changes. We do not rely on permanence or fixed space. People survive in smaller and smaller physical spaces but with a psycho-geographical perspective of ‘the city’ (Beekmans and Boer, 2014). Our experience with Project House signifies how city users are more receptive to new activities and short-term programmes. This creates opportunities for public life-orientated innovations to occur, such as pop-up events that can create social life and add value to vacant spaces.